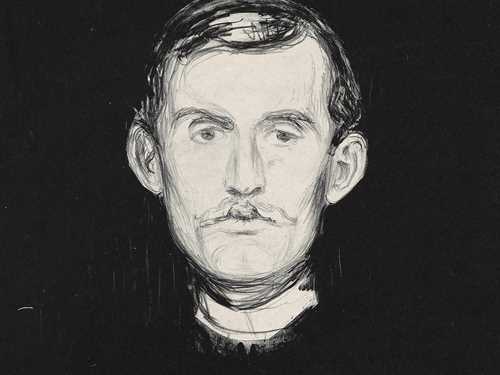

The story of Edvard Munch and the dog Rolle

A classical Norwegian neighbour quarrel.

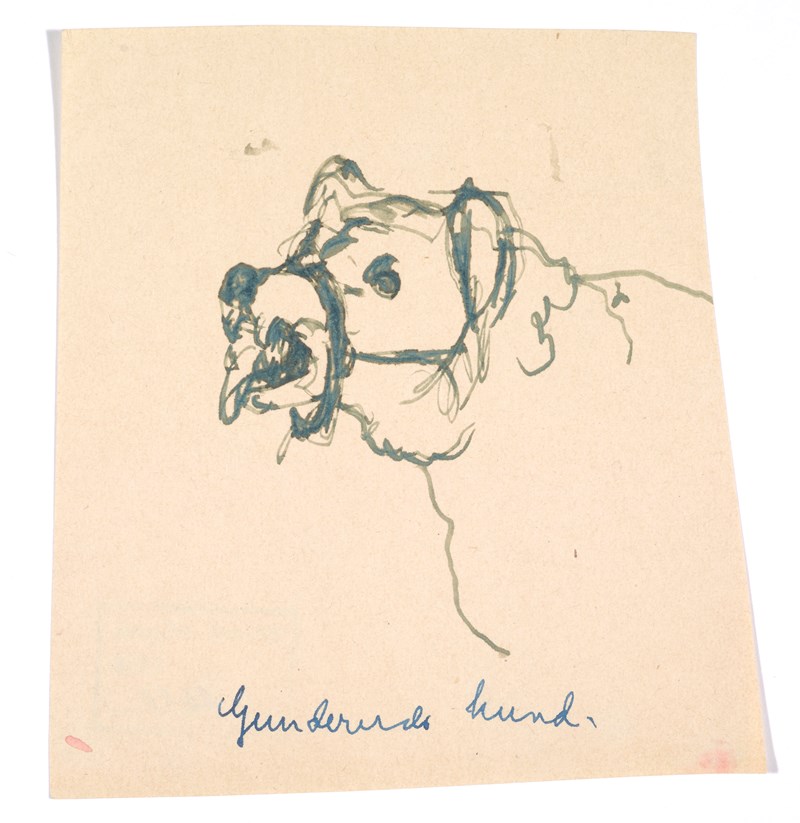

Edvard Munch: Angry dog. Watercolour, 1938–43. Photo © Munchmuseet

Next door to Munch’s home at Ekely, where he lived from 1916, lived a man named Axel Gunnerud and his dog Rolle. Edvard Munch was himself a dog owner, and very fond of the four-legged, but exactly "Gunnerud’s dog", which was the title he consistently referred to Rolle with, he had nothing special to spare.

Rolle had a traumatic childhood. His first owner, a farmer named Mr. Schumacher, fell ill and Rolle was neglected. When Axel Gunnerud first was asked to take over the dog after Schumacher’s death, he was very skeptical. At Schumacher’s, Rolle had always been chained up, was teased and tormented by the workmen, never allowed to run free and play with other dogs, eventually becoming traumatised and wary of people. "If I walked through Schumacher’s gate in those days, it would look as though it was about to eat me alive, furious and baring its teeth."

Nevertheless, Gunnerud took responsibility for the dog. And after what Gunnerud has described as an eight-day nightmare after the takeover, the relationship between the dog and his new owner developed to become intimate and affectionate.

Bitten in the leg

However, Edvard Munch writes: "To begin with, I would stress that Gunnerud’s dog, outside Gunnerud’s house and a good way further up the road leading to other houses is utterly dangerous – This is what it thinks it is supposed to be defending. […] I have myself many times on dark nights been attacked by it – even right outside my own house."

We don’t know exactly what triggered the neighbor quarrel that followed, but it seems quite certain that both Munch and the boy who delivered milk in the neighborhood got bitten in the leg by Rolle. Both neighbors and postmen complained about this to Munch, and the painter decided to "take the case".

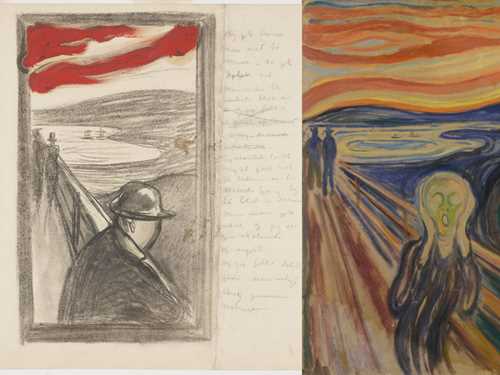

Edvard Munch: The Dog Jumps a Man, pen on paper 1938 (?) Photo © Munchmuseet

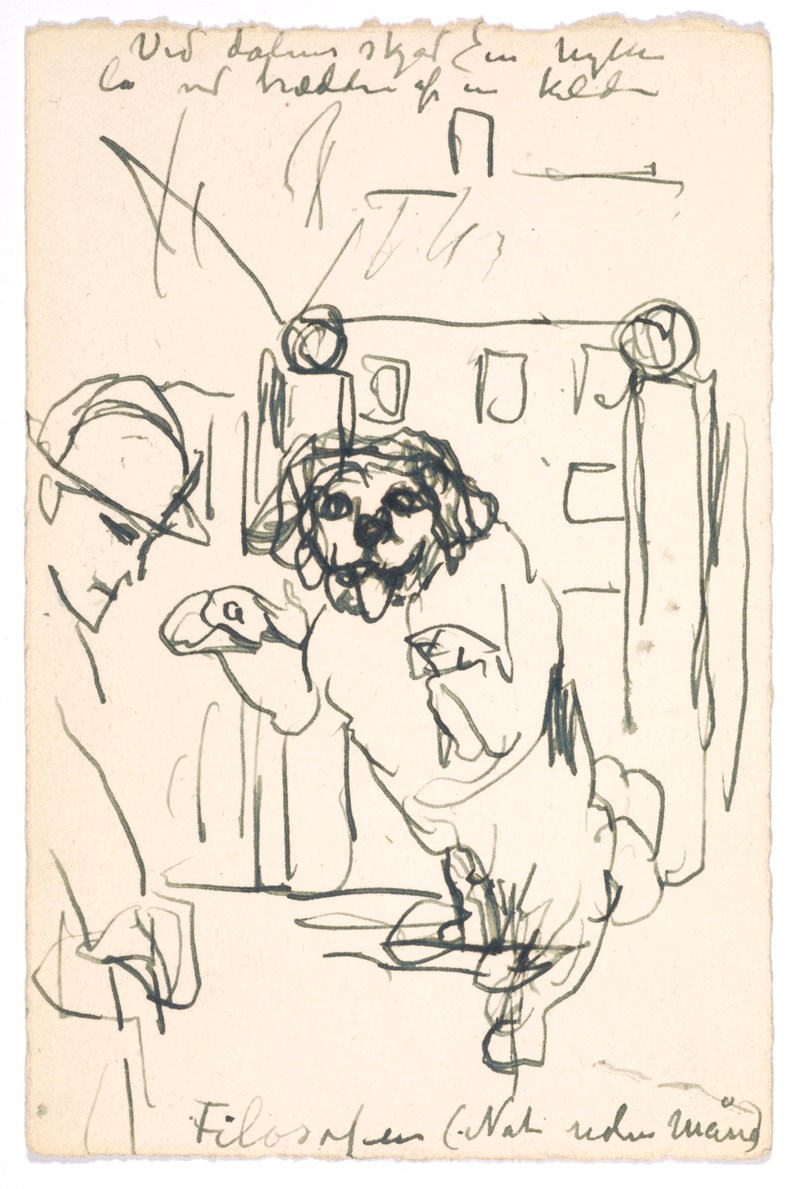

Strongly encouraged by the neighbors Sudmann and Finne, he decides to report Gunnerud to the police. After a while, the neighbor is fined and sentenced to have a muzzle on Rolle. The rules for restraint were also specified. But: «When Gunnerud […] was ordered to put on a muzzle [sic!] (and also a leash I believe) he had a sort of strap put on the dog – and thereupon allowed it to run free – The strap was put on as he saw fit – so it hung loose around the dog’s jaws – with the result that it could still happily bite people’s legs. It also ripped the trousers off the fifth postman.»

The neighbours reconsiders

The leash was also, at least according to Munch, laxly implemente: "The rope gradually became worn and the dog wandered about freely with Gunnerud and with a greater and greater distance between the dog and Gunnerud – Gunnerud became a centre around which the dog moved about freely in a gradually increasing radius […] morning and afternoon – until the dog would turn up as far down as Skøien – and the centre Gunnerud was not to be seen at all."

Edvard Munch: Dog with muzzle (Gunnerud's dog - Rolle), pen on paper ca. 1920. Photo © Munchmuseet

Encouraged by support from the law, and irritated by Gunnerud’s failure to implement what had been agreed, Munch keeps up the fight against the savage creature. But when Axel Gunnerud Axel Gunnerud composes a friendly, elegantly-worded circular letter which he sends to all the neighbours concerned, except Munch, it turns out that several of them have become accustomed to, and perhaps even developed a soft spot, for the dog.

Gunnerud writes: "If there are others [besides Munch] who are bothered by the dog and wish to have it put down, I shall immediately take due and proper account of this." A couple of neighbours add the odd critical comment about Rolle’s temperament and appearance (“I don’t like the look of it; but the poor creature can’t help that”), yet no one wants to have it put down. Even the milk boy’s father expresses some understanding of Rolle’s behaviour. Gunnerud encloses these comments with a letter to Munch – also friendly and elegantly worded – in which he expresses the hope that “my dog will [not] be more of a nuisance to you than it is to my other neighbours.” He also offers to change the muzzle: “Should you not feel reassured by the type of muzzle I am using – which by the way is the usual type – I am most willing to try another kind.”

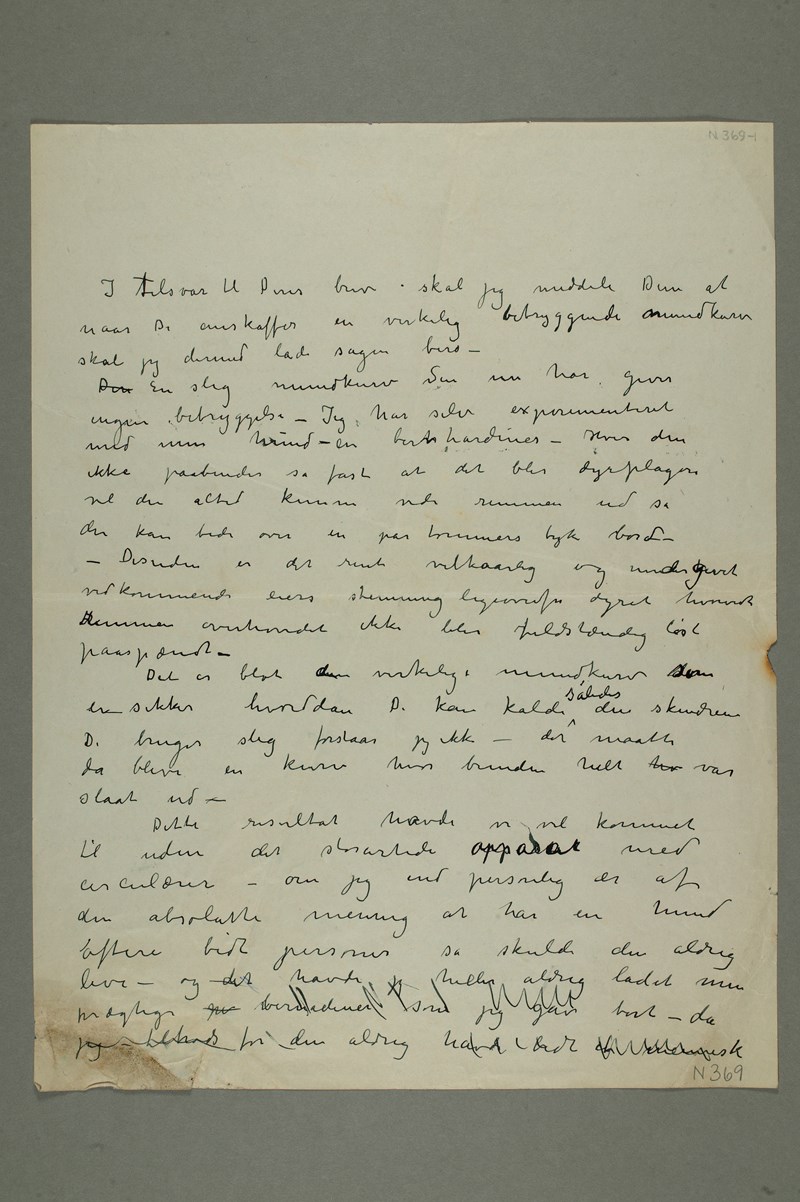

Edvard Munch: Page from letter to Axel Gunnerud. Photo © Munchmuseet

"Or I must sell the place and go somewhere else –"

However, anyone who believes that Munch would be influenced by the fact that former allies have turned their backs on him should think again. It merely whets his appetite, and he reports Mr. Gunnerud to the police again. Munch then receives a visit from the minions of the law, who apparently ask him the inappropriate question whether he has been bitten, or knows of anyone else who has been bitten, since he previously reported the matter. It is no doubt highly awkward for him being forced to answer this question as he writes at least twelve drafts of the letter to the police, in which he argues that lack of further bites does not count. Rolle is undeniably a dangerous dog.

From one draft to the next, he polishes the wording to give greatest possible weight to his views: “So it is actually just myself and my friends whom the dog threatens – and when the Police ask whether the dog has now bitten or attacked other people, it would therefore seem to be I and my friends who are to be bitten – After the countless incidents – I and my friends do not intend to expose ourselves to this ordeal any longer – So we must either take a car if the state of the road allows or make long detours – Or I must sell the place and go somewhere else –”

Mr. Gunnerud is spared further sentences, and again tries to extend a conciliatory hand to his quarrelsome neighbour. In a new letter, he imposes even more restrictions on himself and the dog, and repeats his offer of a new type of muzzle. And finally, Munch reluctantly gives up the fight against Rolle: "In response to your letter, I will inform you that when you acquire a really reassuring mouthpiece, I will thus leave the matter to chance -". This is followed by several pages of repetition of the old accusations, before concluding: “With this, I hope the hot Punic war is over. Another thing is that most relieved would not only be your neighbors - but also you yourself - and most of all the dog even if it was killed by a well-aimed shot. "

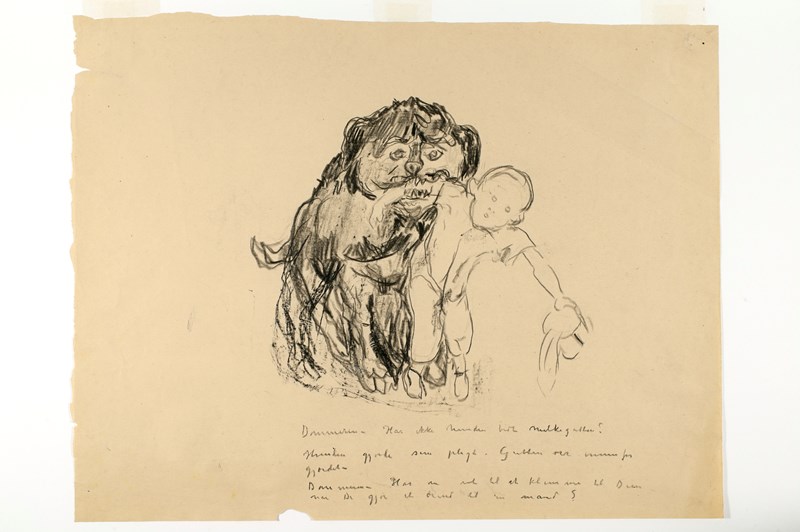

Edvard Munch: The Dog Attacks the Milkboy. Crayon, 1938 (?) Photo © Munchmuseet

Exhibited the dog drawings

After this, the quarrel and the exchange of letters stopped. But Munch, whom was known as a fierce and confrontational type, kept complaining about other issues. There are similar, long correspondences with other recipients in MUNCH’s collection of letters. Opponents were often caricatured in cartoon form, and in parallel with the neighbor quarrel about Rolle, Munch also illustrated this case with a number of sketches.

Most of the drawings were probably done long after Rolle had been put to rest, and the lithographs were not printed until after Munch’s exhibition at Holst Halvorsen’s in 1938, which included some of these drawings. This shows that the memory of this little dispute between neighbours stayed with Munch for the rest of his life, and perhaps even gradually grew in importance. At any rate, Rolle certainly did so: In the drawing The dog attacks the milk boy , Rolle, whom Gunnerud described as “a type of Norwegian farm dog”, is considerably larger than the poor milk boy, and in Angry Dog he looks like a monster which even a large Norwegian bear would have avoided taking on.

The article is based on the text "The story of the dog Rolle, a classic Norwegian neighbour quarrel", written by Magne Bruteig to the launch of Edvard Munch's drawings catalogue.