What can Munch teach us about creativity?

Edvard Munch never stopped improving his motifs, embracing new techniques and exhibiting his experiments while they were still in progress. Here are eight things he can teach us about creativity.

1. Nothing is wrong

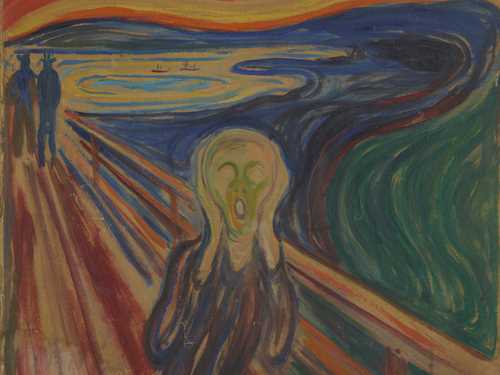

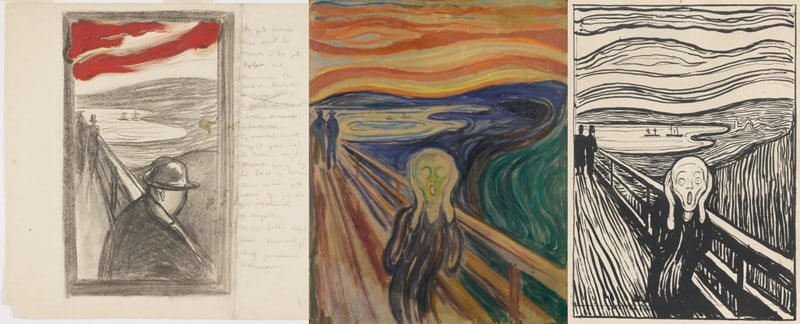

Perhaps we have Edvard Munch’s limited formal art education to thank for his lack of concern about what was wrong and right in art. It seems as though such concepts did not exist in his world. At the start of his career Munch encountered objections that his paintings were “unfinished” and painted in “crazy colours”, but as he demonstrated repeatedly, there was more than one way to realise a motif.

Sometimes this would be about strong colours, other times about composition, and yet other times about how paint was applied. In Munch’s prints, the shapes tended to be highly simplified. “All of my pictures are studies and preparations for new works,” he wrote in one of his many sketchbooks. To Munch there was no right or wrong way of making a picture, but there were always new ways.

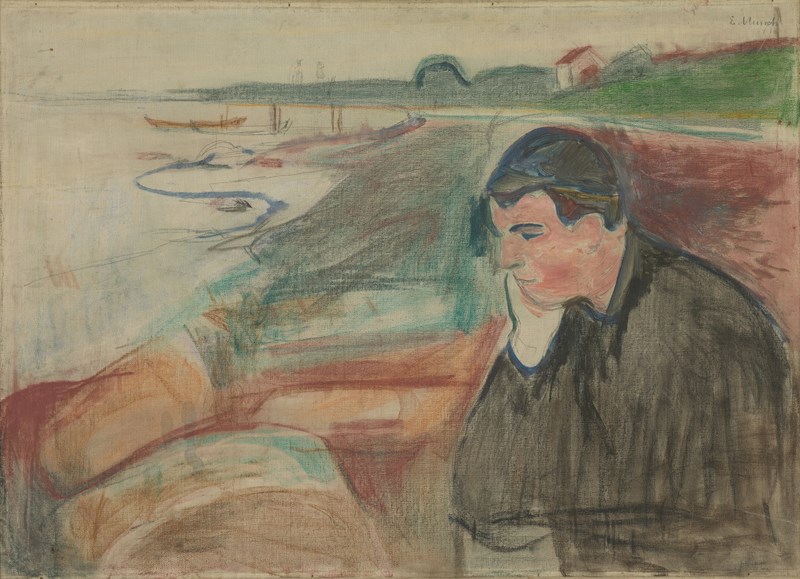

Munch used different techniques creating this version.

Edvard Munch: Evening. Melancholy. Oil, pencil and color pen on canvas, 1891. Photo © Munchmuseet

2. Borrow from others

Munch’s artistic practice never stood still. Even as a student he took his sketchbook and painting equipment out into the streets, influenced by fellow artists who were painting outdoors. He also took inspiration from the author Hans Jæger’s challenge to “write thy life”, translating personal experiences into universal motifs in his pictures.

Munch adopted the ideas of the French Impressionists, painting fleeting visual impressions from the streets of Paris and his hometown of Kristiania (now Oslo). In Berlin he discovered the possibilities of printmaking, teaching himself the various techniques – etching, lithography and woodcut – at record speed. Whether it was the possibilities offered by the film medium or theories about metabolism in the natural sciences, Munch pursued a never-ending quest for new ideas and working methods. He took whatever he could use and adapted it in his own way. The result was always his own.

This motif was painted after Munch lived for a period in Paris.

Edvard Munch: Karl Johan in the Rain. Oil on canvas, 1891. Photo © Munchmuseet

3. Dare to go for it

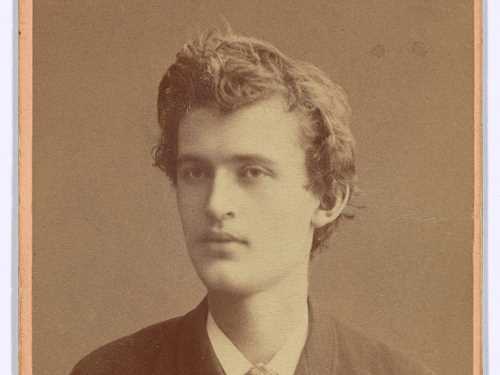

In 1889, when he was 25, Munch did something unusual for a young artist. He rented a hall at the Student Society in the centre of Kristiania, and filled it with his paintings. The daring move gained Munch wide press coverage and helped him win a state travel grant.

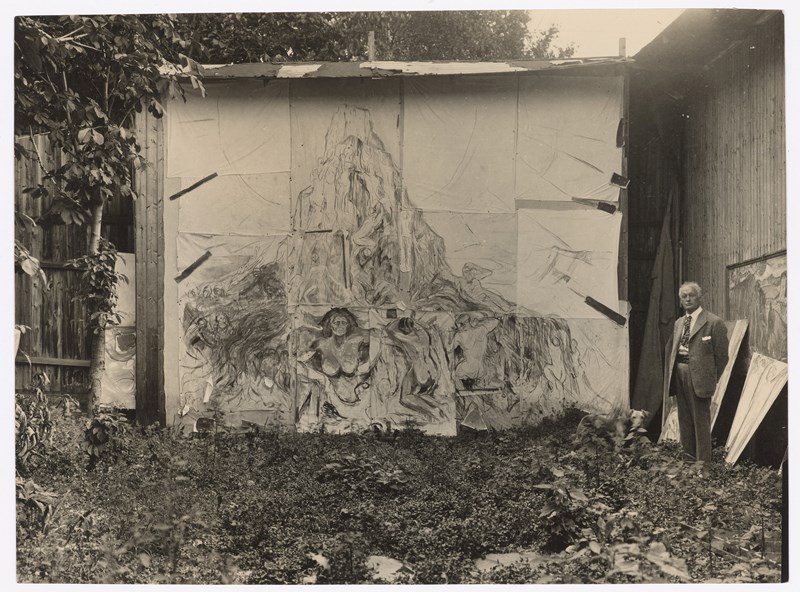

When he returned to Norway in 1909 after many years abroad, he entered a competition against several others to win the commission to decorate Oslo University’s ceremonial hall, the Aula. Munch created several hundred drawings, oil sketches and variations in order to win the commission. He also made half-size versions of his proposed compositions that he exhibited in both Germany and Norway. His efforts secured extensive press and attracted public interest. In the end, it was Munch’s paintings that filled the walls of the Aula.

Munch working on a version of The Human Mountain.

Photography of Munch's open-air studio. Photo: O.Væring Eftf AS © Munchmuseet

4. Don’t hide your process

In 1892, Munch turned the Berlin art scene on its head with his “scandal” exhibition. His “sketch-like” and “unfinished” pictures shocked critics and public alike, and the exhibition was closed after less than a week. Munch quickly turned the attention to his own advantage and continued to exhibit elsewhere in Berlin. Often he rented his own venues which not only allowed him to keep the admission fees, but afforded him the chance to experiment with different ways of hanging his pictures.

Over several decades, Munch used exhibition spaces as a laboratory to conduct research into his own art. Sometimes he exhibited sketches alongside what visitors considered to be more finished works, or he would hang unframed paintings as a frieze high up on the wall. Whatever the result of these projects, they were never undertaken in vain. “I don’t regret works in which I’ve developed further,” wrote Munch.

Munch displayed this pastel version with a more "finished" painting of the same motif in Berlin in 1893.

Edvard Munch: Death in the Sickroom. Pastel on canvas, 1893. Photo © Munchmuseet

5. Be an entrepreneur

From quite an early age, Munch tried to earn money from his art. During his first year at the Royal School of Art and Design, he attempted to sell three small nature studies at auction, but ended up having to buy one of them himself. He drew newspaper cartoons to help with the family finances, but nor was this venture particularly successful. These attempts show Munch’s willingness to think creatively about how he could use his art to make a living.

Printmaking was undoubtedly the area in which he was most successful financially, and allowed him to distribute his most in-demand motifs widely. In particular, his Madonna lithograph was a bestseller and exists in several hundred printed impressions. However, this was about far more than profit. Munch made changes to his printing plates while printing, so that his motifs also evolved during the process. In this way, printmaking became another source of his artistic development – and perhaps the most important.

Edvard Munch: Madonna. Lithograph, 1895. Photo © Munchmuseet

6. Keep your experiments

Munch was not particularly good at getting rid of things, and this is a trait that we should be grateful for today. His hoarding is one of the reasons why Munchmuseet owns more than 28,000 paintings, prints and drawings. At the time of Munch’s death his life’s work was scattered around his Ekely estate, in studios and outbuildings. “You see, I never use the wastepaper basket. I have used my suitcases,” he wrote to a friend a year before he died. “That’s why it is so awfully difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff, but also why I’ve kept so much.”

Our ideas about which of Munch’s works are his most important do not necessarily coincide with his own. Often he abandoned a painting or a subject, only to return to it years later and develop it further. The Museum is working constantly to highlight new sides of Munch’s artistic practice, and to challenge preconceptions about how we perceive his pictures today.

The first time Munch exhibited this motif, there was a plant with a fetus between the couple. He later changed the painting.

Edvard Munch: Metabolism. Oil on canvas, 1898–1899. Photo © Munchmuseet

7. Forget all the others

Although Munch was influenced by ideas and trends of his own times, he also did his own research. In his younger years he would sometimes socialise to the point of exhaustion, and then withdraw and immerse himself in his artistic endeavours.

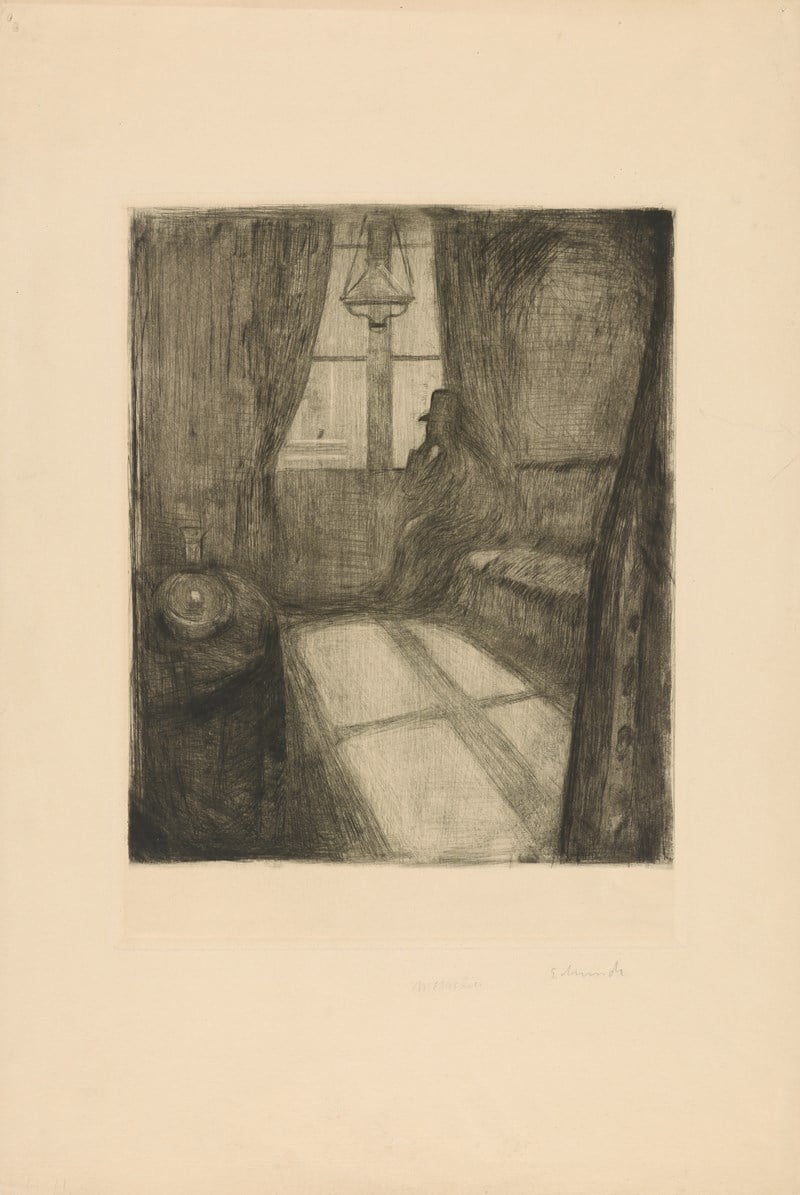

Perhaps the clearest example of this was when he lived in the Paris suburb of Saint-Cloud in the winter of 1890. Munch’s father had just died, his travel grant had almost run out, and he was concerned about his health in the approaching cold and damp. These circumstances made him unable to bear the company of other people. From this difficult period, Munch derived new ideas about his art, in which the depiction of what was fundamentally human became his core concern.

Even though his later artistic practice never ceased to evolve, this concern remained constant. As Munch summed it up himself, in one of his many notes “Naturalism, Impressionism, Symbolism are movements that have become means of expressing a single concern, the human“ (1892-94).

Is this Munch's room?

Edvard Munch: Moonlight. Night in Saint-Cloud. Etching, 1895. Photo © Munchmuseet

8. Keep what makes you distinctive

Right from the time he exhibited his first painting at home in Kristiania, Munch was the object of criticism. “With Munch’s pictures, the level of the current Autumn Exhibition is dragged very far down,” asserted the newspaper Aftenposten in 1886. At his Berlin debut in 1892, his paintings were interpreted as a veritable insult to art.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to place Munch in the role of misunderstood genius, but things were not really that bad – he was praised by other artists and described as a “singular talent”. Even so, he tirelessly stuck to his convictions and did not yield to criticism. Eventually Munch was rewarded. His major international breakthrough came in Cologne in 1912, in a major group exhibition devoted to modern art, including recently deceased masters such as Van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin. Two living artists were invited to participate: Picasso and Munch. “I am quite classic and pale,” wrote Munch cheerfully of his entry into the canon of modern art.

Cupid and Psyche was one of the pictures featured in the exhibition in Köln. The oil painting has since been exhibited over 40 times in both Europe, Asia and the USA.

Edvard Munch: Cupid and Psyche. Oil on canvas, 1907. Photo © Munchmuseet