5 things you should know about The Scream

It is one of the world’s most famous artworks, a universal symbol of anxiety and it even has its own emoji. Here are five clues to understanding Edvard Munch’s most celebrated motif.

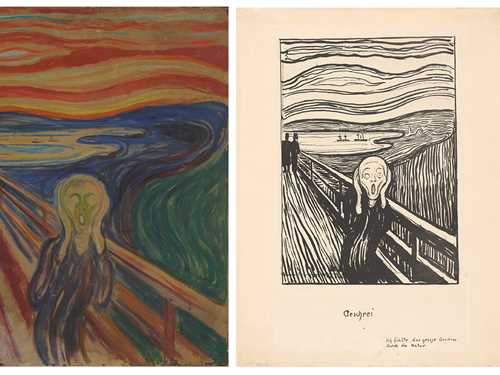

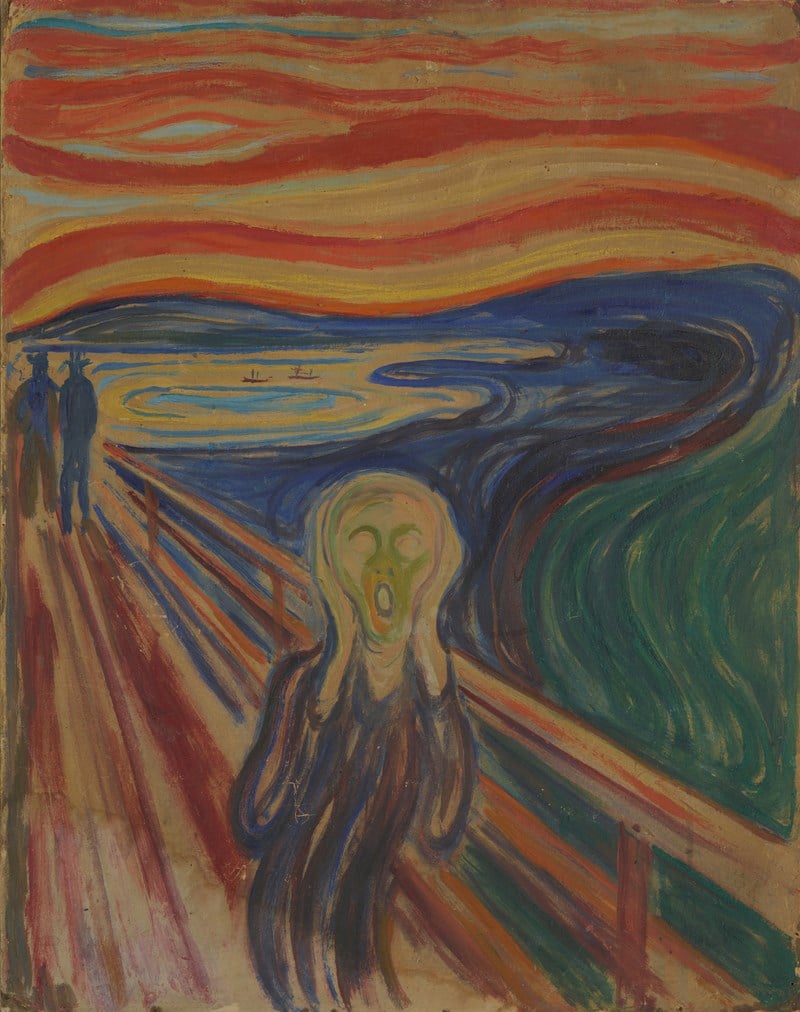

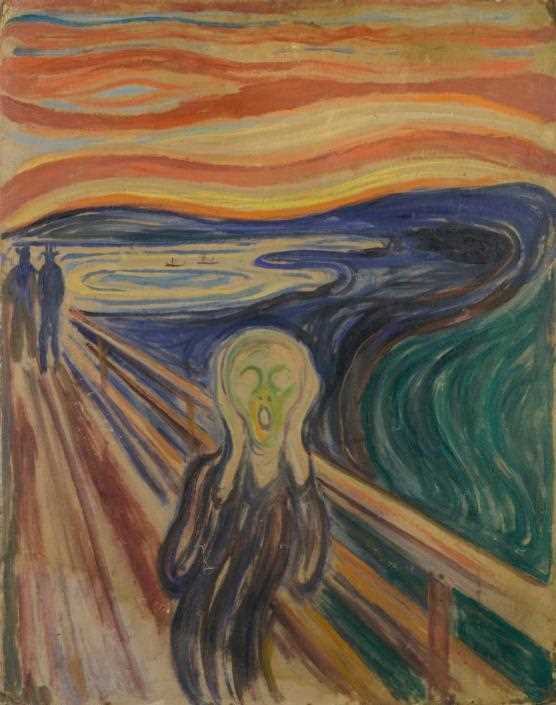

Edvard Munch: The Scream. Tempera and oil on unprimed cardboard, 1910? Photo: Munchmuseet.

1. There are several versions of The Scream

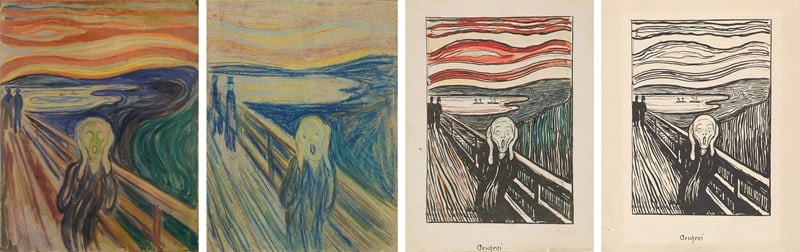

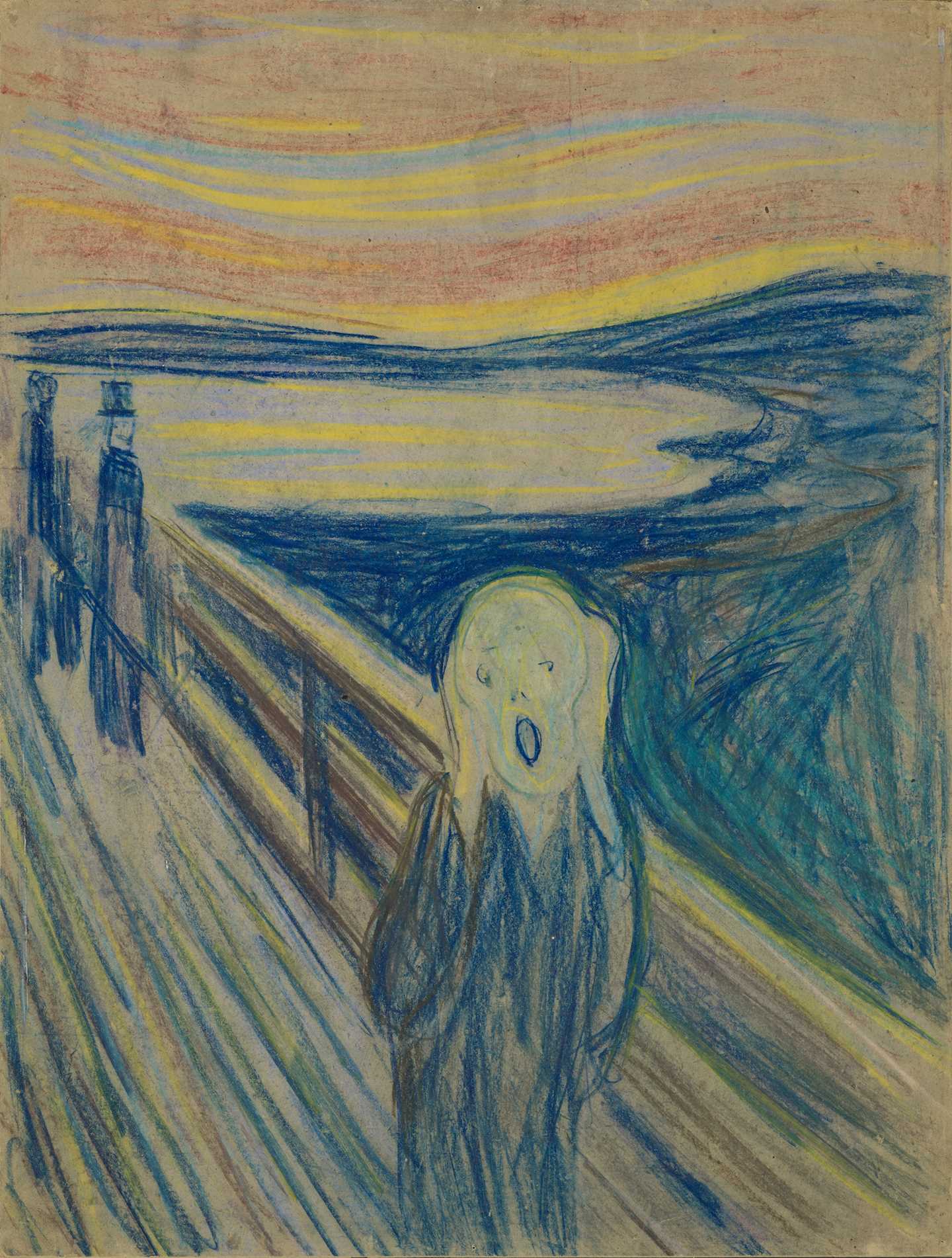

Munch’s most famous motif apparently started with a walk he took with two friends around sunset. The colourful spectacle provoked a strong reaction in Munch, while his friends remained indifferent. He tried to come to terms with this happening by putting it down on paper both in words and images, resulting in several versions of The Scream. As was the case for other artworks, Edvard Munch produced various versions in order to satisfy the demands of his clients, or to keep one for himself: four Scream versions, two tempera paintings and two drawings, of which two remained in his own possession and are in the MUNCH collection today.

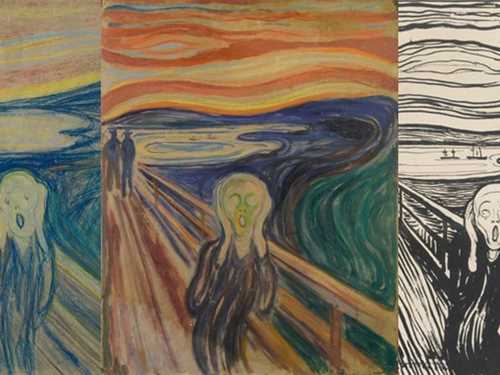

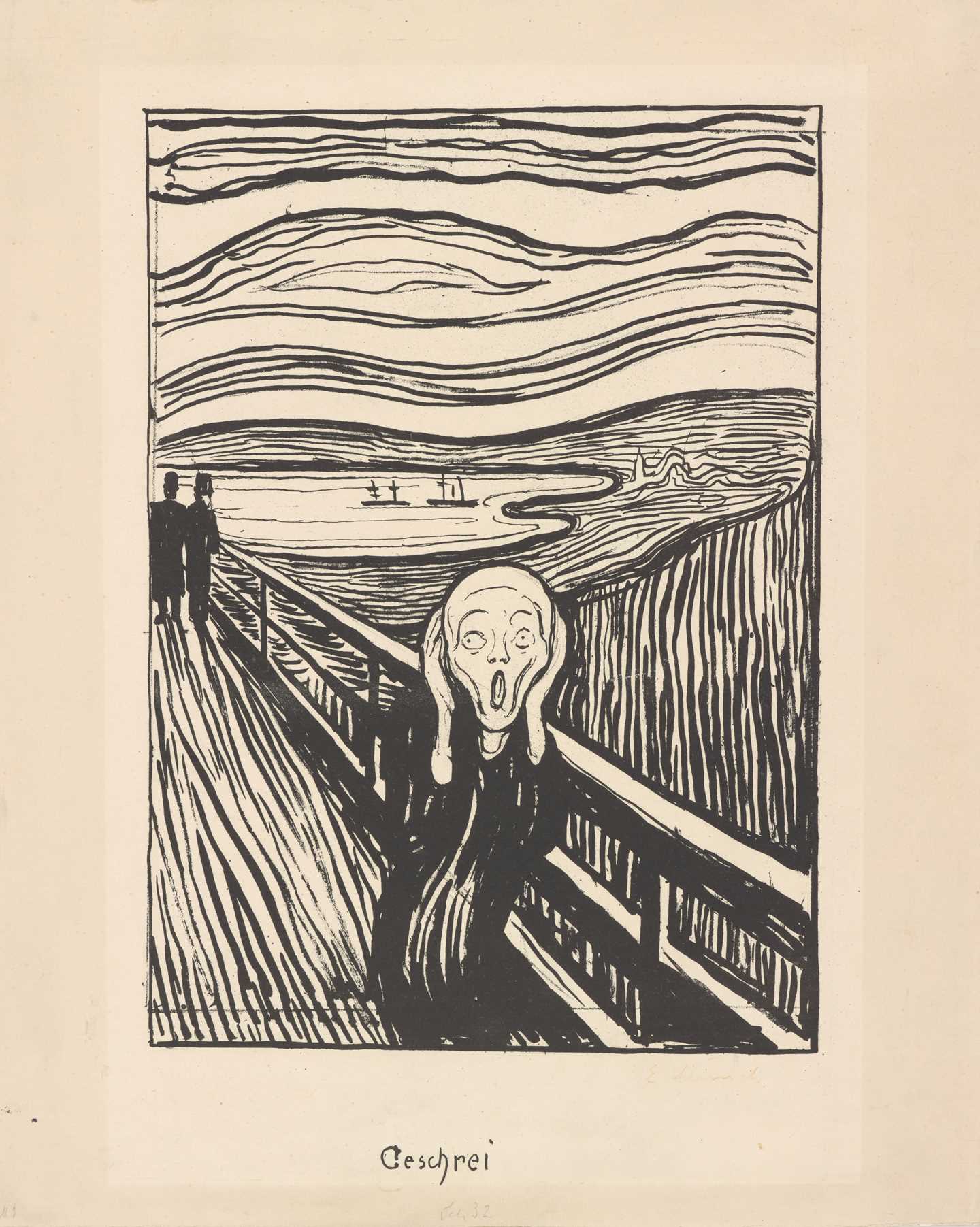

Munch also created a lithograph of the motif, in which the curvilinear pattern of the sky is as evocative as in the paintings. We don’t know how many lithographs were printed, but we estimate that there are around 30 impressions of The Scream. Six of these, including one that was hand-coloured by Munch, are in the museum today.

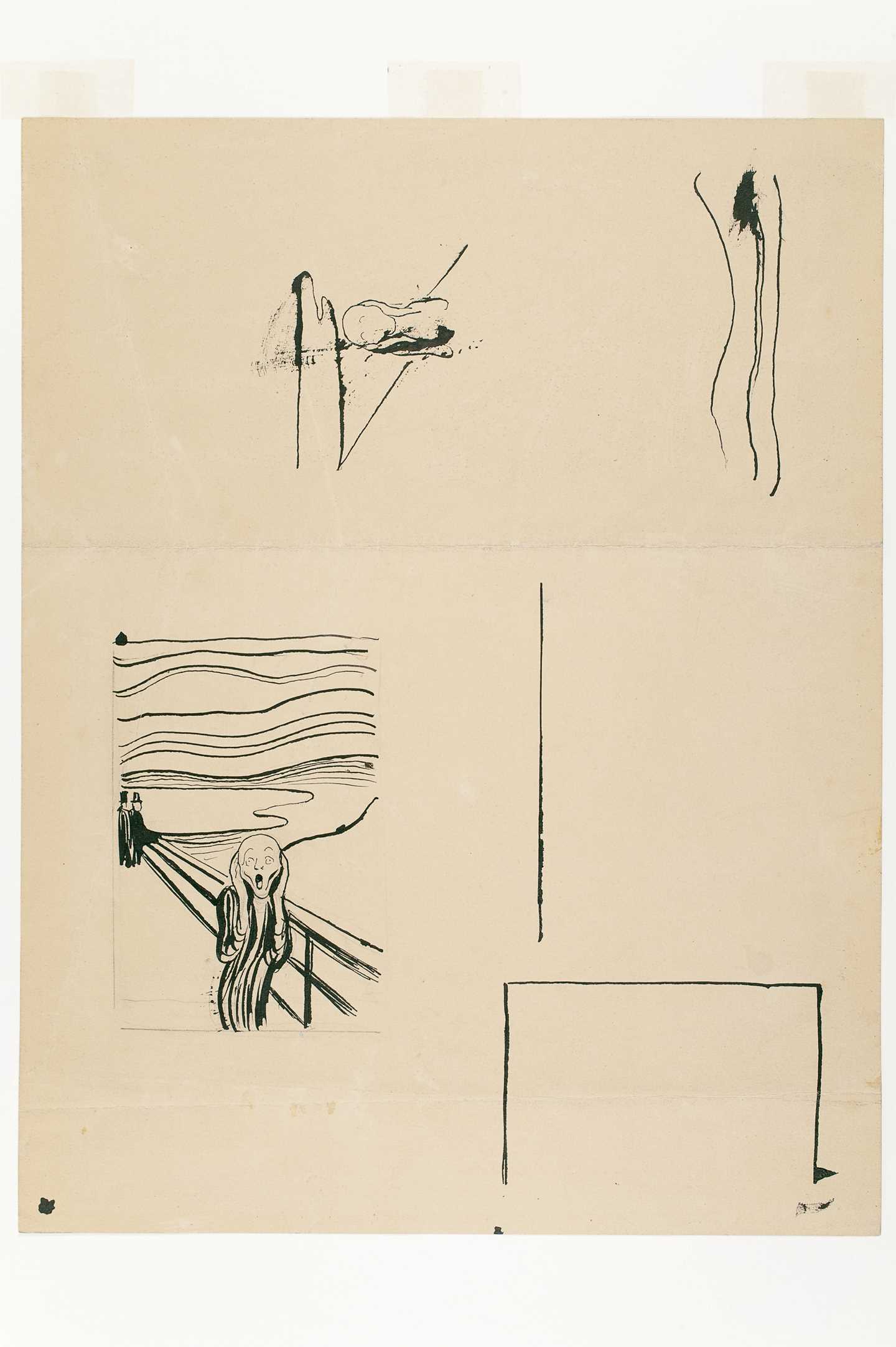

4 of the museum's 8 versions of Edvard Munch's The Scream: A painting with tempera and oil on unprimed cardboard, probably from 1910, a drawing version with crayon from 1893 and 2 of the museum's 6 lithographs from 1895, the one to the left a hand-coloured version.

2. The Scream is a riddle

Although Munch’s most iconic work, The Scream is still a riddle both in content and form. There is no single interpretation of the distorted figure in the foreground. Are we watching someone actively screaming, or somebody reflexively reacting to a scream? Are we looking at a real person, or a symbolic representation? The figures in the background, minute as they are, seem to hold the key to the image. Submerged in conversation or in their own thoughts, they continue walking without turning around. Notice how cleverly Munch underlines the predictability of their progression by placing them on an absolutely straight road. Assuming that the two are neither blind nor deaf, they must either be ignorant or the spectacle simply does not reveal itself to them.

What we are witnessing is a classic case of miscommunication: one situation, two contrasting reactions, and no interchange. We often act like these figures, following our chosen path without looking left or right. It is as if Munch is saying, or rather screaming, that it is time to stop and look around.

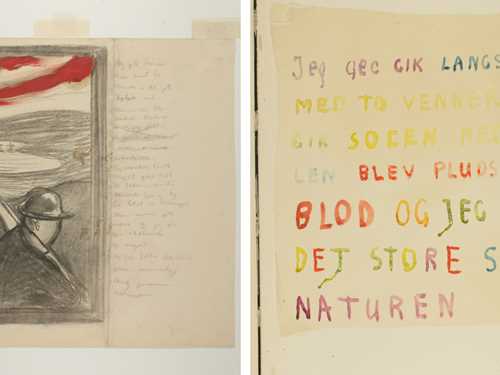

3. The Scream is also a text

Before The Scream transformed into an image, it took shape as a text. In Nice at the French Riviera in the winter of 1892, Munch recorded a poem in his diary, describing the walk with his friends. He was captivated by the view of the flaming clouds and the blue-black city and water. Shivering with anxiety, sensing «a great and infinite scream through nature.», he had to stop.

In the same year, Munch translated the experience visually. Interestingly, when he sold one of the pastel versions of The Scream, he attached a short version of the prose poem on the front of the frame. The lithographic version of The Scream was printed together with a short quote in German from the poem. However, this quote has often been trimmed off and is now missing on a good number of impressions. In 1928, Munch published the full Scream text in a booklet on his life-long project The Frieze of Life. In addition there are eight further versions in Munch’s unpublished notes and diaries. We can therefore assume that the text engaged Munch as much as the image.

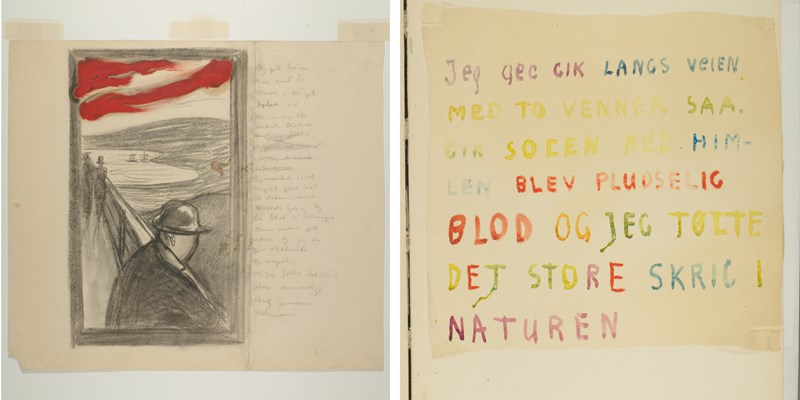

From Edvard Munch's sketchbooks: Left: Despair, with version of The Scream text. Coal, oil, 1892 (probable).Right: Handwritten text. "I was walking along the road with two friends". Watercolor, circa 1930. Photo © Munchmuseet

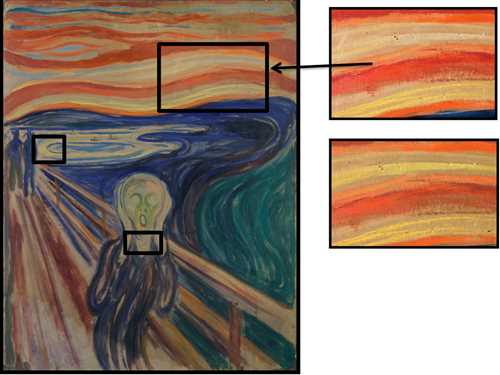

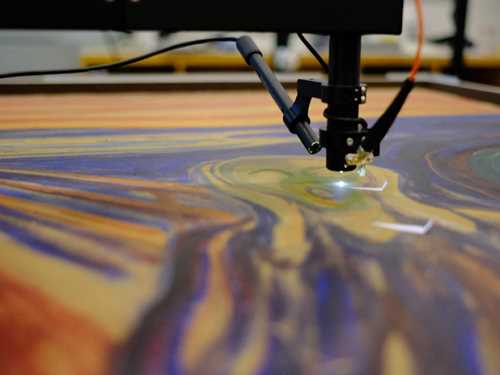

4. The Scream needs to be cared for

The Scream may be a powerful motif, but every one of its versions is an extremely vulnerable artwork. Whether painted, drawn or printed, they all contain relatively unstable materials that sooner or later may react negatively when the works not being kept in dark and climate-controlled storage.

This knowledge presents us with a conflict at the Museum: on the one hand we wish to show and share Munch’s most iconic artworks, while on the other we wish to preserve them for many generations to come. And as so often in life, the solution rests in a compromise: Based on meticulous scientific research on the material properties of all the version The Scream, we have developed a finely balanced rotation system, ensuring that none of the versions are being overexposed.

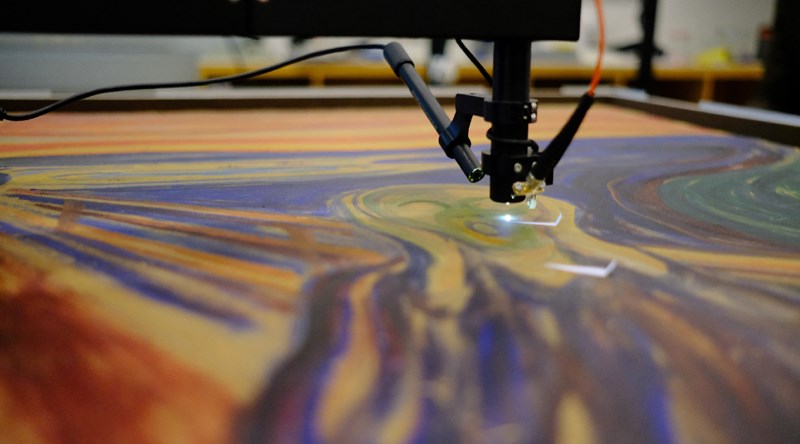

Microfading of The Scream. Photo: Tomasz Łojewski

5. The Scream has a double-life

It was the printed version of The Scream that was picked up by the media and reproduced almost instantly. This simple, yet strong image was reproduced in journals such as the French La Revue blanche in 1895 and the American M’lle the year after. In 1908 it was also to feature as a cover illustration for a book on psychological disorder and art.

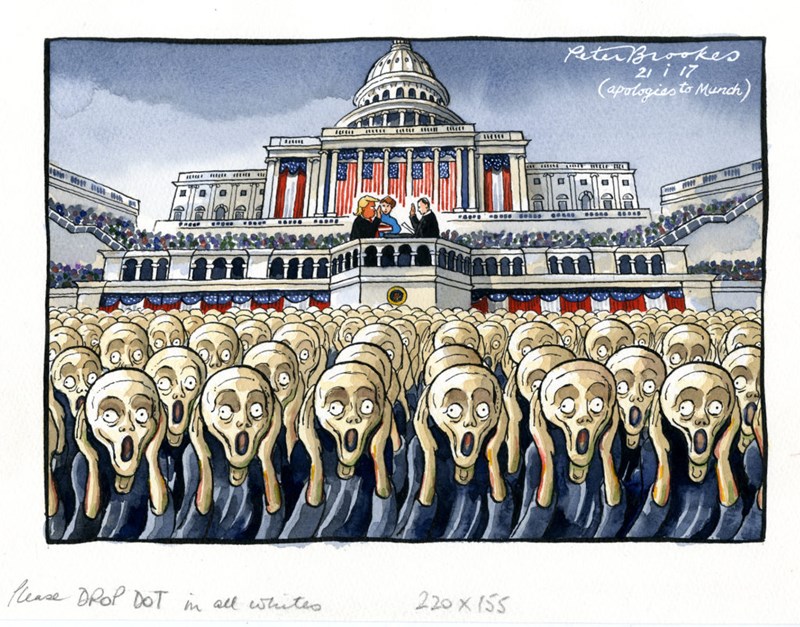

The motif’s early popular status has constantly received boosts – in recent decades culminating in uncountable adaptions of the main figure in popular culture. Subjected to two spectacular robberies in 1994 (at Oslo’s National Museum) and in 2004 (at Munchmuseet) and one hair-raising auction record at Sotheby’s in 2012, the motif has regularly secured global headlines. The main figure’s distinctive gesture is generally understood as an expression of horror. This makes it easily employable for all sorts of visual communication, ranging from topical caricatures in mass media to personal messages in emoji sign language.

Peter Brookes (f. 1943), The Scream, 2017.