Edvard Munch’s sensitive lungs

Did you know that Edvard Munch owned his own inhaler? And that he was afraid of being infected with lung disease his whole life? At the museum we look after a large number of the artists' personal items – some more surprising than others.

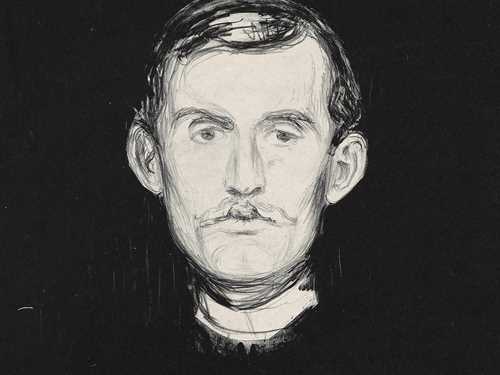

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait. Oil on canvas, 1940–43. Photo © Munchmuseet

When Edvard Munch died, a strange contraption was found in his house. It consisted of a tank of oxygen and several mouth pieces, and was probably used to treat Munch’s lung problems, which he had suffered from since childhood. It was a state of the art device which came with comprehensive instructions, bought from a German pharmacist in Berlin in 1921.

We don’t know how well it actually worked for Munch, but it is now in the museum’s collection.

A vulnerable organ

Lung diseases ran in Munch’s family, taking the lives of Edvard’s mother Laura and his elder sister Sophie. Munch himself lived in constant fear of getting infected.

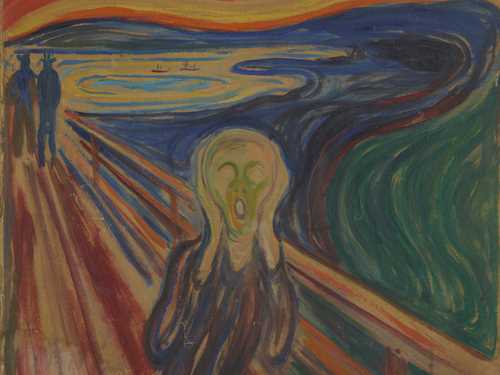

Edvard Munch: The Sick Child I. Lithograph, 1896. Photo © Munchmuseet

The Munchs were also not the only ones who were plagued by lung diseases. At the turn of the nineteenth century, lungs became the most vulnerable of human organs. Tuberculosis in particular led to millions of deaths until a cure was found after the Second World War.

Suffering sex symbols

Until 1882, when the bacteria that causes tuberculosis was discovered by the German microbiologist Robert Koch, the illness was imbued with mystery. Since so little was known about the disease, it developed a rich cultural life of its own. In artistic and intellectual circles tuberculosis was idealized as a mark of heightened sensitivity and artistic talent. The phthisic look – emaciated figure, pale skin, feverish eyes – became fashionable. The composer Frédéric Chopin and the virtuoso violinist Niccolò Paganini were morbid sex symbols. Less attention was paid to their suffering and their terrible deaths.

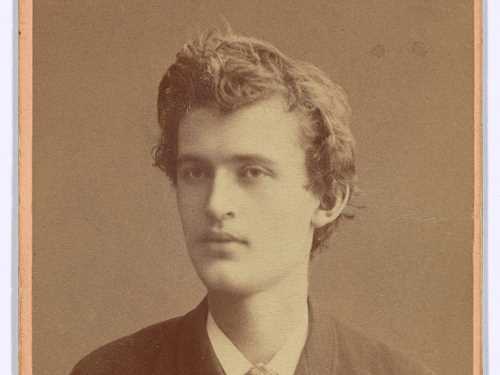

Edvard Munch: Death in the Sickroom. Lithograph, 1896. Photo © Munchmuseet

The journey towards better health

Since there was no cure for tuberculosis, all one could do was to create a healthy environment to keep the infection at bay. Those who could afford it travelled to southern Europe during the winter months, where the climate was warmer. From the mid-nineteenth century onward, it became fashionable to spend time at high altitude. This was the heyday of lung sanatoriums, which were built in the Alps. Following strict routines, the patients spent as much time as possible outside, where the thin, pure mountain air was regarded as having a beneficial effect on the lungs.

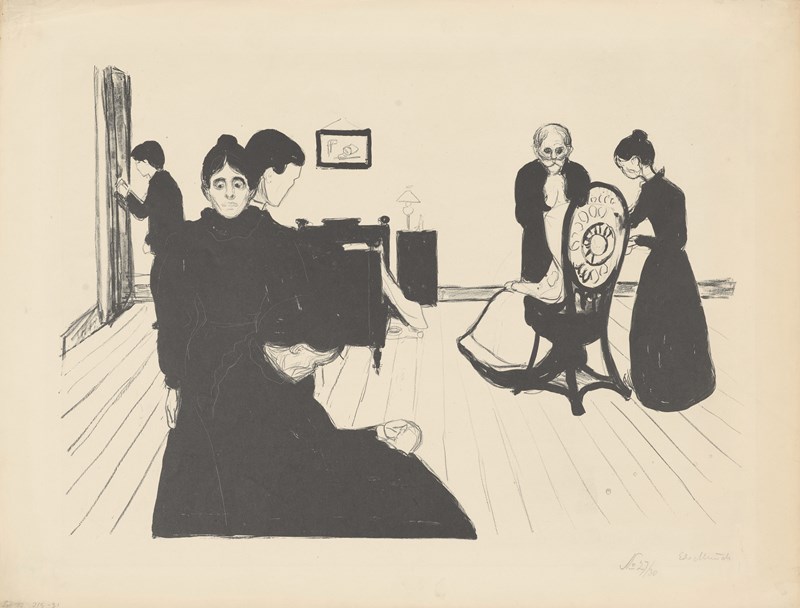

Patients at a sanatorium in Davos, about 1900.

A social problem

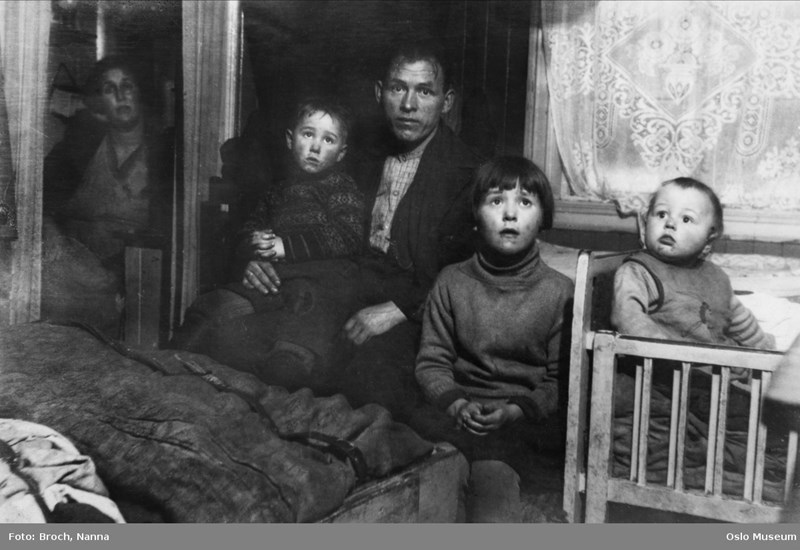

By the end of the nineteenth century, tuberculosis had become a disease of the working class and therefore a social problem. It found a perfect breeding ground in workers’ neighbourhoods in the big European cities, where residents lived under devastating hygienic conditions. In 1944, Selman Waksman and Albert Schatz developed an antibiotic for treating tuberculosis. This, together with improved hygiene, led to a significant decline in the numbers of deaths and new infections. Today, at least in developed countries, tuberculosis is widely defeated and forgotten. In other parts of the world it is still a serious problem causing more than a million deaths each year.

A working class family in Oslo in the 1930s. Photo: Nanna Broch

Last breath

Munch never got tuberculosis himself, but he lived with the fear of the disease all his life. In the end, it was a more common lung disease that ended his life. One winter evening, he went out into the garden at Ekely, probably with too little clothes on. He got a cold and never recovered completely. The cold gradually developed into a bronchitis, then pneumonia, until Munch was too weak to get out of bed. He drew his last breath at the age of 80.