The history of the Museum

The new museum building at Bjørvika has certainly provoked a lot of debate, but the original museum at Tøyen also generated significant controversy in its time.

The Museum at Tøyen at its opening in 1962. Photo @ Teigens fotoatelier/Dextra photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum

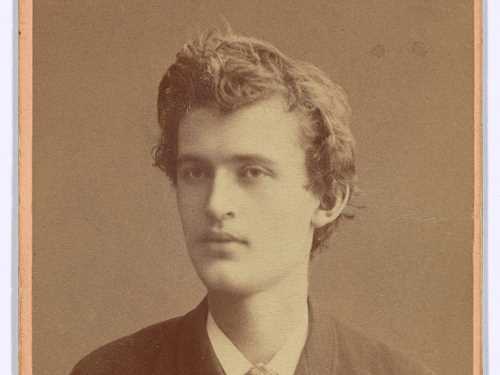

Four years before Edvard Munch died on 23 January 1944, he made a will leaving his entire estate to the City of Oslo. This hugely generous and diverse bequest consisted, among other things, of more than 28,000 artworks, as well as texts, letters, photographs, equipment and other personal possessions.

Discussions about a future museum had begun while Munch was still alive, and with his involvement, but it was only in 1946, two years after his death, that the City of Oslo approved the building of a museum. The debate about the Museum’s location took off from day one: Should it be near the Vigeland sculptures in Frogner, or closer to the centre, adjacent to the Royal Palace? Or perhaps it should be at Grünerløkka, where the artist had spent the formative years of his childhood?

Ambitions and reality

The director of the City of Oslo’s art collections, Johan H. Langaard, had high ambitions for the new museum building. Langaard believed that the bequest had given the City a “sacred moral duty to use its best endeavours for a world-class genius and his posthumous reputation”.

But Langaard was also politically astute, and attempted to build a bridge between international ambitions on the one hand, and ideas about the proper nature of a municipal museum on the other. As a municipal museum, the building should not be too flashy, and it should combine exhibition space with a workplace, with plenty of space for the employees. When it became clear in 1951 that the Museum would be located at Tøyen, he adapted his plans to the sloping triangular plot, even though he had originally hoped for the Frogner option.

Finally, in 1953, the architectural competition to design the Museum was announced. Fifty entries were received, and a proposal titled Rondo Amoroso by the relatively young architects Gunnar Fougner (40) and Einar Myklebust (30) won the first prize and NOK 10,000. Critics suggested, however, that the judges had attached too much weight to municipal and social-democratic considerations, to the detriment of the Museum’s international ambitions.

The debate about the Museum’s design and content continued throughout the construction period. Some people complained that there had been a failure to create a setting of international status for Munch’s art. Others, such as the architect Georg Eliassen, pointed out that the choice of plot had been the subject of political horse-trading. He noted caustically that the location “was chosen perhaps more with the idea of distributing cultural assets from an urban-planning point of view than out of consideration for the thousands who in the future will seek the way to Edvard Munch.”

Outdated on opening

When Munchmuseet opened its doors in May 1963, 100 years after Munch’s birth, it met almost rapturous acclaim in the press. It soon became clear, however, that the building was inadequate for the institution it was intended to house. Staff numbers grew rapidly, and in fewer than 20 years the need for upgrades became critical. The Museum’s then-director Alf Bøe described the building as an “economy building” which had proved “not to fulfil expectations”. The increasing interest in Edvard Munch’s art had clearly been underestimated.

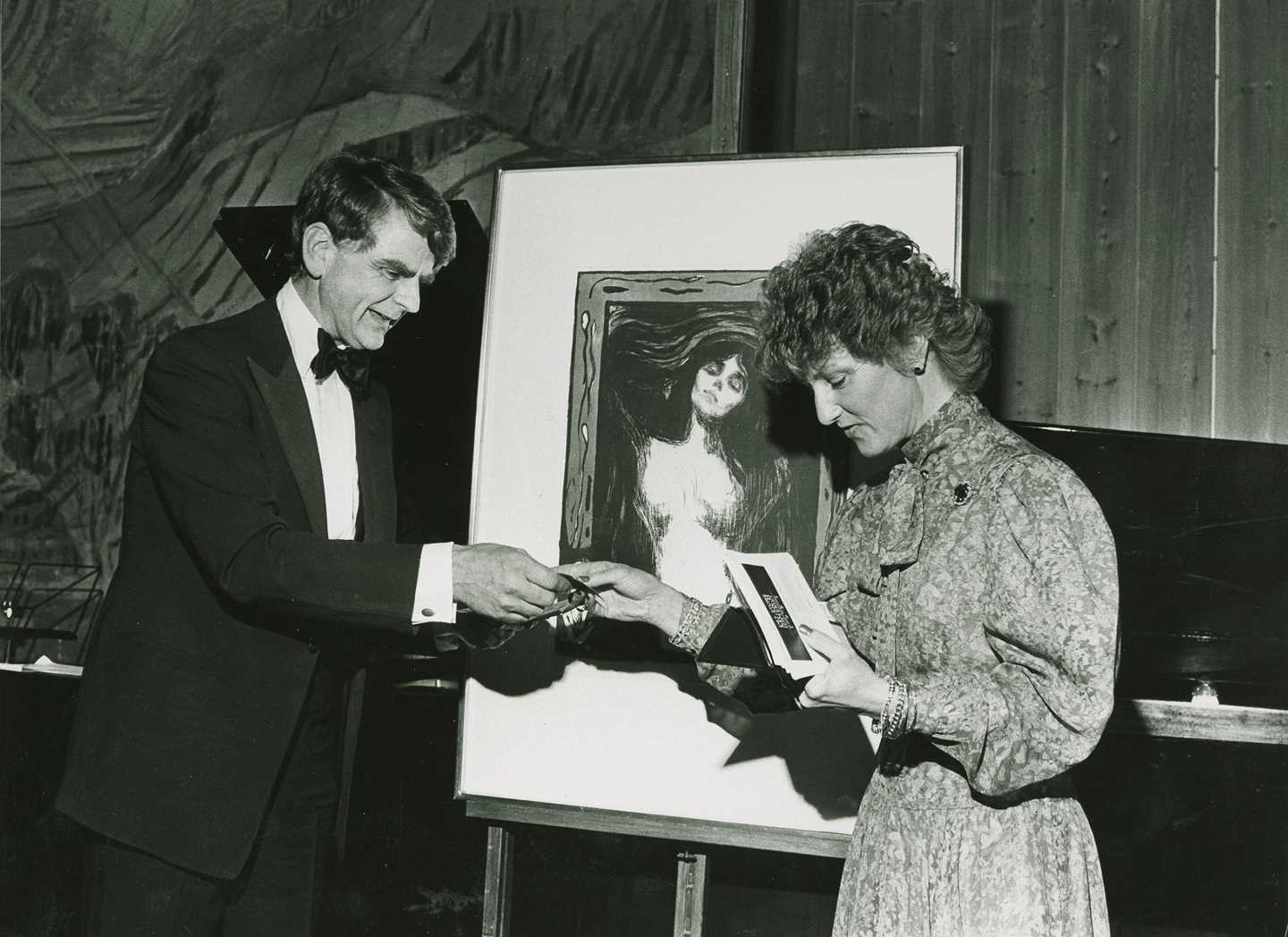

At the same time, extending the Museum would require a great deal of investment. Throughout the 1980s the Museum engaged in a major quest for external funding, with various initiatives. In 1989, consideration was given to erecting a new building on the original Frogner plot next to the Vigeland Museum, instead of extending the existing building at Tøyen. Nonetheless, in the end the building at Tøyen re-opened in 1994, with a new entrance section, a new administration section, and general refurbishments.

A robbery and upgrades

On 22 August 2004, the American broadcaster Sky News paused its scheduled programming, while both the BBC and CNN cleared time for several minutes of live reports from Oslo. The reason was that two masked gunmen had entered Munchmuseet and escaped with two world-famous paintings: The Scream and Madonna. After a report by Det Norske Veritas concluded that the building was only at “a very low level” suitable for housing Munch’s works, the Museum closed its doors for several months to implement improvements. When the building reopened in May 2005, there were airport-style metal detectors and an optical scanning system for checking tickets. The most important artworks were covered with protective glass and the wire hanging system had been replaced with wall-mounted fixings.

On 31 August 2006, the Oslo police proudly informed the press that the two paintings had been recovered after an armed police operation. Despite the upgrades made to the Museum, however, there was an inexorable move towards closing the building at Tøyen. Finally, in 2008, the City Council resolved that the Museum should move and a new architectural competition would be held. This decision acknowledged that the building once intended to be the ideal Museum had never fulfilled this goal. Soon a new debate about location had begun.

Read more about the new Museum building, in which Edvard Munch’s unique bequest will finally have the home it deserves.

This article is based on "The physical setting" by Martin Braathen from the publication "EXIT! Stories from the Munch Museum 1963–2019", which is available from the museum shop.