Admir Batlak – “In the Kink” (2023)

Anti-fascist monuments, fashion and queer culture in the west have inspired Admir Batlak’s new installation at MUNCH. This essay, by curator of contemporary art, Tominga O’Donnell, explores some of the SOLO OSLO-artist’s wide-ranging references and exhibition history.

Admir Batlak is the first artist selected for SOLO OSLO from an open call.[1] His new work for the distinctive gallery space on level 10 of MUNCH is remarkably consistent with his initial ideas. In his interview with the jury in June 2022, Admir spoke about his ambitions of scaling up his sculptural practice, and how he has been inspired by Yugoslavian anti-fascist monuments throughout his life. Admir arrived in Norway at the age of 11, having left Bosnia and Herzegovina with his family following the outbreak of civil war in the Balkans (1991–2001). His background is in fashion, and he spoke of how he would choreograph his shows to create “live installations” and fleeting “aesthetic moments”. He spoke of western gay culture and how cultural codes are made manifest in textiles. He had a glimmer in his eye as he spoke of “deceitful surfaces” and playing with people’s expectations.

BROTHERHOOD AND UNITY

Admir’s earliest points of reference, which continue to inform his artistic practice are the many monuments created across the Balkans in the aftermath of the Second World War. Spomeniks were erected to celebrate the “brotherhood and unity” of the new Yugoslavian republic under Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980). One such monument was constructed in Admir’s birthplace of Mostar, and designed by the architect Bogdan Bogdanović (1922–2010). It differs from many of the other spomeniks typified by huge concrete structures in futuristic, abstract forms.

Miodrag Živković and Ranko Radović, The Battle of Sutjeska Memorial Monument Complex in the Valley of Heroes, Tjentište, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia & Hercegovina (1971). Photo courtesy of Donald Niebyl and the Spomenik Database.

The Mostar spomenik is also a cemetery and part of Bogdanović’s plans for a sprawling necropolis. The vast stone and concrete memorial site was opened by President Tito in 1965 on the 20th anniversary of the liberation of the city of Mostar to commemorate the anti-fascist Partisan fighters who had lost their lives. Damaged during the Bosnian War (1992–1995), the memorial site was rehabilitated in the early 2000s. In 2006, it was proclaimed a national monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In recent years, the Mostar spomenik has been the target of nationalist graffiti and vandalism as it sits in disrepair, a decaying monument over a traumatic and complicated past.[2]

SCULPTURAL TEXTILES

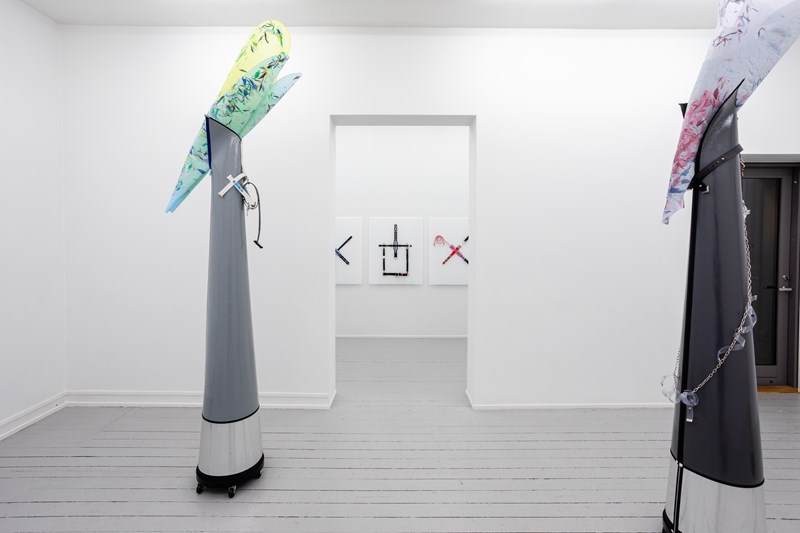

The spomenik use of abstracted forms of wings and flowers can be seen in some of Admir’s earliest sculptures in the series A New Tomorrow (2019), first shown at Galleri Riis in Oslo. The five sculptures were made entirely of layers of different textiles, often used in the fashion industry, fused together with vliesofix, a layer of thermal glue, which allows two fabrics to be attached to each other using an iron. For A New Tomorrow the base layer is cotton canvas, which is then bonded together and laminated with metallic PVC in different shades of grey. The insertion of a zip enables the creation of a bouquet at the top of the sculptures that echo those of the spomeniks. Each petal of the “flower” is made up of different coloured feathers, pressed between two layers of sheer fabric – tulle and organza. The effect was inspired by the scattered multicoloured remains of feather boas in the street after Pride celebrations in Oslo. Each sculpture had a harness with metal studs, inspired by fetish wear. Each sculpture was its own entity and placed on casters so that the constellation could shift. Three of them featured in the Annual Autumn Exhibition (Høstutstillingen) at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo a year later. The display earned Admir the Norwegian Art Associations’ debutant’s prize, and his work travelled to Skiens Kunstforening, Khåk Kunsthall in Ålesund and Bodø Kunstforening.[3]

Admir Batlak, A New Tomorrow, Galleri Riis (2019). Photo by Adrian Bugge.

CONSTRUCTION

Galleri Riis has been the site of Admir’s shifting between the realms of fashion and fine art. After graduating from Istituto Marangoni in Milan where he studied Fashion Design in 2006, Admir set up a partnership with Charlotte Selvig. They collaborated between 2007 and 2010, and Batlak & Selvig earned many a number of awards, accolades in the fashion press and stints working for Dolce & Gabbana. They showed work at Galleri Riis in 2008, and after they split Admir continued to show his collection there, moving increasingly into what he referred to as “live installations”.

There are elements of these live installations in how Admir choreographs his sculptural work, including the outdoor ones he created for the Norwegian Sculpture Triennial, curated by Silja Leifsdottir, in 2021. In these three sculptures, Admir expanded on his interest in the component parts of fashion and those used in the construction industry. The base of each sculpture was created from Lurex, a type of yarn with a metallic appearance, which was made to look like wet concrete through the application of melted PVC. A similar PVC lamination onto sequins provided a shimmering base layer for three columns in red, white and blue – the colours of both the Norwegian flag and that of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992). The top of the sculptures consisted of plastic and steel boning, usually used for corsets and crinolines, together with Plexiglas and metal patent bands, fusing haberdashery and industrial hardware. This unveiling of the hidden structures in garments can be directly linked to decaying spomeniks, which exposes their construction, albeit on a different scale and with different materials. Admir’s use of boning, freed from their containment inside restrictive women’s clothing, become cascading or protruding antennae in their own right. Whereas the material might lose its intended function, Admir refers to it as “gaining a super function”.[4]

Admir Batlak, Good Day for Progress 1, 2 and 3, The Norwegian Sculpture Triennial, Oslo (2021). Photo by Adrian Bugge.

IN THE KINK

In his commission for MUNCH, Admir has scaled up his sculptural work to take on the 8-meter-high ceiling of the gallery. Together with Kolab Architects, he has reconfigured the approach to his installation so that visitors meet it head on as they enter the space, rather than from the side. This attention to how the visitor’s first encounter is also central to many spomeniks, which have specially designed walkways that facilitate a particular physical point of view. The gallery on level 10 of MUNCH sits in the building’s “kink” where one wall is at an angle. Admir’s sculpture is suspended from this angled wall so that it looms over visitors as they approach. For the Mostar spomenik he designed, Bogdanović spoke of how it would physically mirror the city whose sacrifice it was commemorating. The foundation of Admir’s installation similarly refers to its surroundings, echoing the undulating aluminium plates that clad the building on the outside of the museum. The small holes in the rectangular metal frames in austere grey become the fixing point for layers of print – on fluffy wadding or tightly wrapped PVC foil – and a wing of cascading drapes of sequins. Admir refers to it as “two poses, one sculpture”.

SEQUINS AND POSES

Sequins first appeared in Admir’s practice in 2015, featuring in his collaborative exhibition with photographer Ingrid Eggen at the now-closed-down Galleri 1857 in Oslo. Forhøst featured her photographs of his garments, juxtaposed with the original textiles in an exhibition that played with the tactility of the material and the idea of poses that were frozen into fixed form. Since then, sequins have become a staple in his artistic practice where their shininess creates shimmering surfaces to his wall-based sculptures.

Admir Batlak & Ingrid Eggen, Førhøst, Galleri 1857 (2015). Photo by Ingrid Eggen.

This is also evident in his solo exhibition, Fake a Patina, DealBreak a Vibe, at SOFT Galleri in 2022, where Admir created an installation of five sculptural wall-pieces, cloaked in sequins. These resembled figures, including one with a flowing deep-blue cape in which strips of crinoline boning protruded from what resembled a torso, echoing his outdoor works for the Sculpture Triennial. Curator and writer Kjersti Solbakken described them as “monumental butterflies”.[5] Admir moulds them into more stable form by using bonding material such as vliesofix or its equivalents with wadding, wool and canvas. By adding layer upon layer, he is “collaging information into a pose” as he describes it, creating sculptures that mimic more solid materials. The surfaces are deceptive, not revealing that they are sequins until the viewer gets close enough to them to touch.

Admir Batlak, Fake a Patina, DealBreak a Vibe at Soft Galleri (2022). Photo by Adrian Bugge.

CRITICAL FASHION

The titles of Admir’s works reflect his interest in language and turns of phrase that hold a certain ambiguity. For his SS17 collection, he cited Boris Orlov as a reference. Orlov was a proponent of Sots Art, who appropriated propaganda slogans and imagery to subvert it in playful ways in the USSR in 1970s. This reference is also evident in Admir’s collection shown during Oslo Runway in 2017, incidentally at the former Munch Museum at Tøyen. Hverdagsintegrering (“everyday integration”) became “the word of the year” after it was used by Prime Minister Erna Solberg in her New Year’s speech in 2016. It was employed to commend Norwegians on helping to integrate immigrants and refugees through everyday activities such as sport, volunteering and social gatherings. Admir included the term on a pageant-style sash over a look that bore resemblance to the Norwegian national costume, bunad. However, he altered the neologism to its adjective form, thereby marking the wearer as “integrated into the everyday”. The blank expression typical of a fashion model became a barb directed at the insidious assimilative tenor of the self-congratulatory Norwegian term.

Admir Batlak, AW17, The Munch Museum, Oslo (2017). Photo by Trine Hisdal.

A second sash in the same collection bore the word “unorsk” (“un-Norwegian”) a reference to a phrase often invoked by the then right-wing minister for migration and integration, Sylvi Listhaug, to separate out behaviour that was deemed “un-Norwegian”, usually with reference to foreign nationals, who had failed to integrate and were deemed a threat to the Norwegian way of life. At the same time, the term has been reclaimed by others as something positive: when something is “un-Norwegian” it is refreshing, unmarred by cloying conformity that suffuses much of public life in this Scandinavian social democracy. In a further ironic twist, these two of the works were acquired by the National Museum of Norway in 2019, and thus form part of the Norwegian design collection and national canon.

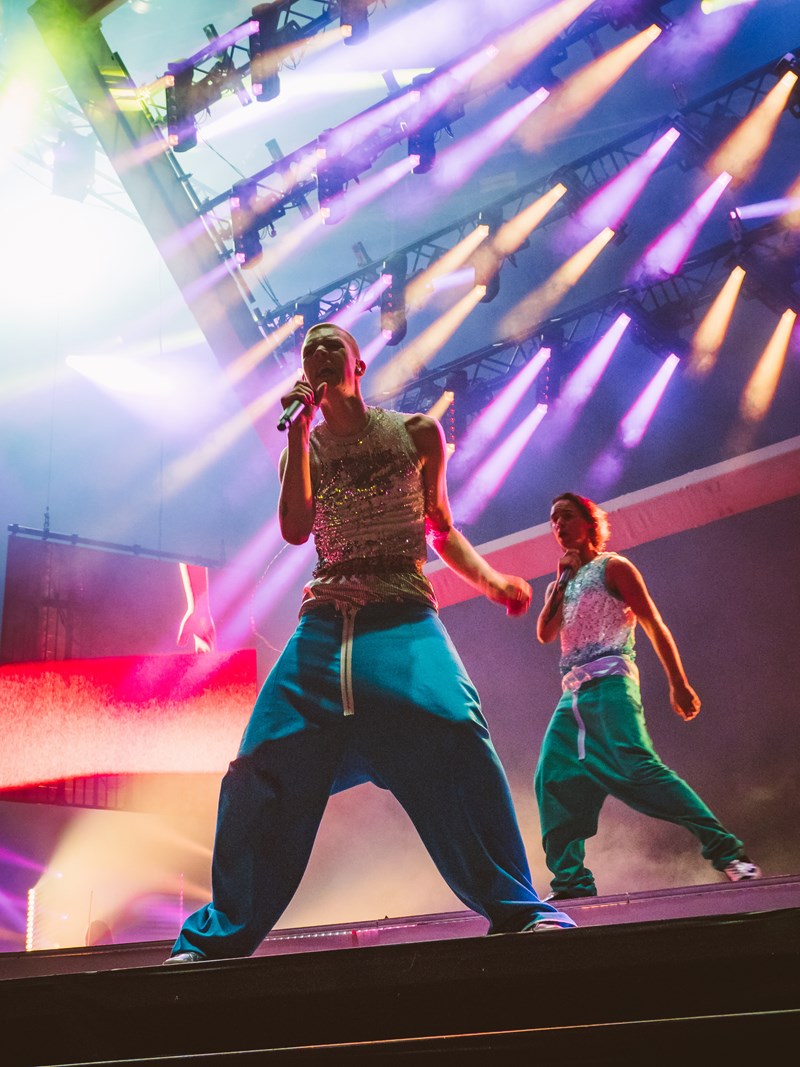

As the final project under his eponymous fashion label, Admir created custom stage outfits for Norwegian singer Cezinando’s closing performance at Øyafestivalen in Oslo in 2018. Here, sequins were central to all four of the looks he created for the musician, mixing the macho connotations of drop-crotch hip-hop trousers with a shiny cape made of pink sequins. The notion of “messing with mainstream masculinity” recurs when Admir talks about his work, and there is an implied rebuke in both his couture for Cezinando and his collection shown at the Munch Museum to mainstream culture and gender normativity.

Cezinando concert, outfits by Admir Batlak. Photo by Christoffer Krook (2018)

EXPANSIVE INSTALLATION

There is return to tailoring in Admir’s exhibition at MUNCH. In a novel move, the installation also encompasses uniforms for the invigilators, inspired by workwear and by the outfits worn by young Yugoslav pioneers at sporting and celebratory events. This wearable extension of the sculpture is relatively austere, a quiet contribution to the mood of the space typical of an artist who reflects on the entirety of how his work is perceived. However, sparkling elements from the sculpture recur in the uniforms, which are bespoke to each wearer, who go from watching over the artwork to become watched as part of it.[6] As they move through the museum on their way to the gallery on the tenth floor, they create temporary tentacles of the work into the rest of the building.

PAINTING WITH THE IRON

Admir’s exhibition at MUNCH is consistent with his earlier sculptural works in his use of bonding materials from the fashion industry. In keeping with his longstanding interest in anti-fascist monuments, he has scaled up the sculpture to take on the large space at the top the museum. There are, however, a couple of new elements in this exhibition, in addition to the above-mentioned uniforms. Firstly, Admir has printed directly onto his haberdashery: the sequins, PVC , vliesofix and wadding.[7] Admir has not only printed onto, but also from photographs of sequins, giving them a strange patina, the ghostly traces of former adornments. When printed onto PVC, the result is a dab-like appearance, evocative of a Claude Monet (1840–1926) landscape painting. The printing on wadding has a fluffy appearance until the colours then spread and splatter as Admir uses an iron to melt parts of the surface in a process he refers to as “painting with the iron”. The second new feature is that he has welded the sequins directly to each other using only their tulle backdrop, rather than repeatedly layering and fixing with bonding agents. As he explains, this means that the effect is much more unpredictable than the controlled ornamentation of earlier garments or smaller sculptures. The combination of scaling up and working in a less constrained way means that there is a great deal of uncertainty associated with this commission for MUNCH, in which the artists is working with materials that have much more agency of their own. Admir expresses trust in the sequin, describing his admiration for its tacky, frivolous, unnatural connotations as a material associated with celebration and joy.

QUEER MEMORIALISATION

A year on from his interview with the jury of SOLO OSLO, Admir is sitting in his temporary new studio: Edvard Munch’s atelier at Ekely. The centrepiece of the installation is taking form, printed-on wadding and PVC panels cover or partially fill their bespoke metal frames, which together make up an arrow pointing in both directions.[8] The installation’s “wing” – the second pose – has not yet been assembled sparkly sequins sit in piles waiting to join their printed-on counterparts. As we discuss how the shiniest ones will affect the overall impression of the sculpture, Admir notes with a shy smile that they are his own little nod to artist Félix González-Torres (1957–1996), who created several translucent bead curtains in gold and other colours in the 1990s. For an artist renowned for creating different sculptural memorials to his partner, who died of AIDS-related illness five years before González-Torres, these are often read as ritualistic, a performative marking of the threshold between life and death, as well as an architectural intervention in the space it is shown. The work is ephemeral and its component parts made of cheap everyday materials, which are regularly replaced. Artist Jesse Darling provides a telling reflection of this in Reliquary (for and after Felix Gonzalez-Torres, in loving memory) from 2022, which consists of two light boxes each half-filled with leftovers from installations by the deceased artist, including candy wrappers, light bulbs, beads and other detritus.

With an entire generation of artists lost to HIV/AIDS their memories are often preserved through this kind of citation. In the absence of traditional monuments, queer memorialisation often functions in this way, through individual homage like Admir’s or Darling’s, soft materials like quilts or fleeting, performative moments – often re-cited and reworked. Think of Every Ocean Hughes’s Untitled (David Wojnarowicz project) from 2001–2007 in which she recreated Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978–1979) wearing a mask of the gay American artist as he had worn a mask of the French author at various sites across NYC. One of these sites was the city’s Pier 52 on the Hudson River, where gay men would congregate to cruise and sunbathe before it was demolished in 1979. Their activities were captured by a number of photographers, such as Alvin Balthrop, and the site inspired the title of Samuel R. Delany’s autobiography The Motion of Light in Water (1988).

MATTA-CLARK’S “ANARCHITECTURE”

I mention the piers, not only because of their centrality to LGBTQI+ history in New York and by extension the Western imaginary, but because they are central to an explicit reference that Admir cites. Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975), in which he cut sections out of the former Baltimore and Ohio Railroad building on Pier 52, is one of the most iconic works in the history of modern sculpture. This work was recently memorialised by David Hammons’s Day’s End (2021) in front of the Whitney Museum, a steel shell built to the exact dimension on the exact site of the original building, like a giant tent without a canvas. Neither work made reference to the piers’ long queer history, other than Matta-Clark complaining that the place was “completely overrun by the gays”[9]. His work on Pier 52 has divided historians and critics when it comes to his relationship with its vagrant occupants and Hammons’s public sculpture has been read as “contributing to the hagiography of a homophobe”. [10] However, one could co-opt Matta-Clark, as Jack Halberstam does in Unbuilding Gender (2018).[11] In this essay, Halberstam picks up on the notion of “anarchitecture”, concluding that “Matta-Clark’s art offers a fantastic legacy to young trans* artists who[…]are less interested in making work within existing parameters for painting, sculpture, and/or performance than in tearing those parameters apart.”[12] For Admir Matta-Clark’s interest in buildings and what they conceal – and reveal through cuts – is relevant to his own work and especially the in the MUNCH commission where the metal back plates of the sculpture echo the museum’s façade.

UNDOING AND BECOMING

Halberstam sees the creative potential in destruction that Matta-Clark espoused through his anarachitecture theories linking them to how “trans* bodies [can] offer fleshly blueprints for the unbuilding of binary understandings”. It is an intriguing proposal that aligns Matta-Clark's ideas with those of Fred Moten and Audrey Lord – cutting into buildings and bodies as a way of eschewing “the master’s tools” (Lorde, 1979) or “‘tear this shit down completely and build something new’” (Moten, 2013). By way of uniting these seemingly diverging views of the Hudson River piers – their role as sites of queer lived experience and of these two straight male artists’ seminal sculptures – I interpret Admir’s references to “messing with mainstream masculinity” as practising a version of what Halberstam is describing. To my mind, Admir is not merely “messing”; he is fundamentally unbuilding in his alternative approach to monumentality by rejecting the materials and tools associated with traditional monuments and instead using shiny sequins, fluffy textiles, elastic and plastic to construct something entirely new – a simulacra monument.

Admir insists on the work being constantly “in process”, suggesting material agency as he describes his sculpture as “on the way to becoming”. It is not seeking to become a monument or to be fixed in a particular form, but to retain its monumentality while resisting symbolic meaning. Admir speaks of the sculpture being in a liminal state, between brand new and already in decay, monumental and fragile, clumsy and fabulous. Despite the artificiality of the main material – plastic – the finished result is remarkably organic. The industrial finish of the sequins is made less glossy by printing directly on them. The sculpture looks almost like an underwater mythical creature, covered in scales. A sea monster with a camp side, showing off its iridescent, golden locks while invoking the nostalgia of monuments to “brotherhood and unity”.

SOLO OSLO – Admir Batlak is on display at MUNCH from 30 September 2023 to 4 Februrary 2024.

Footnotes

[1] The jury was chaired by Steffen Håndlykken and consisted of Amina Sahan, Karen Reini, Tove Aadland Sørvåg and Tominga O’Donnell.

[2] Donald Niebyl writes on the Spomenik Database: “As detailed in volume 40 [1966] of the journal 'Arhitektura urbanizam', this monument at Mostar was meant to represent 'stone', his work at Jasenovac represents 'water', his work at Sremska Mitrovica represents 'fire', his work at Prilep represents 'sky', while his work at Kruševac represents 'earth'” See https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/mostar/

[3] Norske Kunstforeningers debutantpris includes a cash prize of 50,000 NOK and the possibility of showing the work in several art associations (kunstforeninger) across Norway.

[4] All quotes by Admir Batlak are either from my many conversations with the artist or his conversation with Miriam Wistreich as part of #42 HOW TO PRACTICE? ADMIR BATLAK at UKS in Oslo, 15 June 2023.

[5] Kjersti Solbakken, ‘Sommerfugler i krinolinebånd’, Kunst Pluss no 1 (2022), page 50 [my translation].

[6] The garments have been made in collaboration with Aurora Verksted, just outside Oslo, which is an inclusive, mixed-ability workplace.

[7] Admir has worked with the Canon Image Factory in Oslo to create this experimental kind of large-scale print on unusual surfaces such as sequins, wadding and vliesofix.

[8] The steel frames are made by Kampen Mekaniske Verksted, an Oslo-based metal workshop.

[9] ‘ON THE WATERFRONT Peter L’Official on David Hammons’s Day’s End’ in Artforum, May 2021 https://www.artforum.com/print/202105/peter-l-official-on-david-hammons-s-day-s-end-85472

[10] Evan Moffitt, ‘The Invisible Histories of Day’s End’ in Art Review, 4 June 2021

[11] Jack Halberstam, ‘Unbuilding gender - Trans* Anarchitectures In and Beyond the Work of Gordon Matta-Clark’ in Places Journal, October 2018