World-Building and Unbuilding Through a Queer Lens

Liv Brissach takes a close-up look at ideas of world building and queerness in Meriem Bennani and Jacolby Satterwhite’s video works included in the exhibition The Machine is Us.

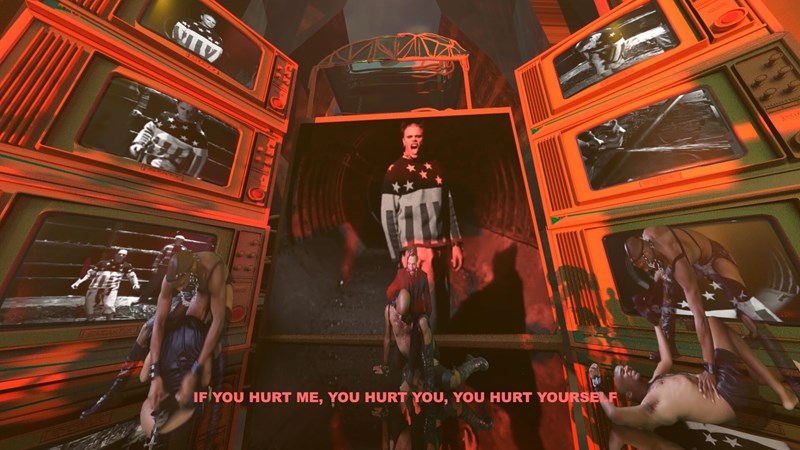

Jacolby Satterwhite: Still from We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020. HD color video and 3D animation with sound © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

In his book Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz described utopian queerness as one that is not yet here, an ‘ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future’. (1) This has been useful in discussions of world-building. With a nod to his late colleague’s title, Jack Halberstam has described what at first seems like the opposite process: one of unbuilding or unmaking, a ‘reimagining of the world from the perspective of taking it apart’.(2) In the lecture Cruising Dystopia, Halberstam proposes unmaking and undoing, rather than construction, in order to move ahead in a late capitalist, unbalanced world of over-consumption and power asymmetries. With these two queer perspectives on building and unbuilding worlds, this text will take a detailed look at two artistic approaches to animation and the moving image from The Machine is Us, on display at MUNCH 01.10. – 11.12.2022.

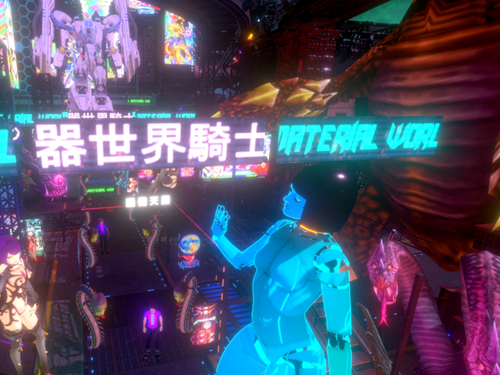

Jacolby Satterwhite: Still from Shrines, 2020. HD color video and 3D animation with sound © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Digital world-building – the process of constructing multi-voice and complex environments with their own intrinsic logic – is a strategy used by several artists in The Machine is Us. These involve digital tools which are highly sophisticated in terms of image manipulation and level of detail, which make for supremely immersive experiences. This is perhaps most keenly felt in the recent works by Jacolby Satterwhite (the immersive moving image works Shrines, 2020 and We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020) and Meriem Bennani (the video installation Party on the CAPS, 2018–19). Both Satterwhite and Bennani build and unbuild worlds, balancing between utopia, realism and critique in order to convey complex ways of being and relating to the world. Both of them, are involved with reprogramming ‘operational images’, to borrow a term from Harun Farocki, another artist in the Triennale, in order to shift from one world to another. The operational image was defined by Farocki, in his work Eye/Machine I (2000), as ‘Images without a social goal, not for edification, not for reflection’, but which very much still cause an action.(3) This tension and pendulum-swing between the liberation and longing found in constructed worlds, with added elements that deconstruct and critique our shared world, is what make these artworks sites of great complexity.

Harun Farocki’s Operational Images

Harun Farocki (1944–2014) was a highly influential moving image artists and theorists of his generation. His interest in the history and politics of the animated image – thematised in his work Parallel I–V (2012–14), among others – is pertinent in the context of the The Machine is Us and in this text. Parallel I–V holds a central position in the exhibition precisely because it builds a foundation from which many of the other works can be understood. In addition to the works by Satterwhite and Bennani which are discussed here, you also find resonance between Farocki and the world-building strategies in Cameron MacLeod and Magnhild Øen Nordahl’s hyper-realistic VR experience Two Rocks Do Not Make a Duck (2022) in the lobby; as well as in Lu Yang’s existential, genderless and spiritual video game The Great Adventure of Material World (2020).

See also: Overview of all the artists in MUNCH Triennale 2022

Harun Farocki, Parallel I–IV, 2012–14 først. Courtesy of Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo

Farocki’s multi-channel moving image work Parallel I–V follows gameplay of a few popular games while a voice-over traces the development of gaming aesthetics across three decades, from primitive two-dimensional renditions to increasingly photorealistic graphics. The tone is theoretical and inquisitive and emphasises representation, physical limitations and movement. Farocki found that the real progression of animation did not lie in the mimetic qualities of the renditions, but rather in the generative algorithms and invisible data at work in constructing these images, actions and reactions in the gaming environment.(4)

In his earlier Serious Games I–V (2009–10), Farocki revealed that this detachment of the image’s appearance and movements from mimetic representation is already deeply embedded in military applications. The operational images of video games are strategically employed to prepare trainee soldiers for the reactions, emotions and situations they might encounter on missions. When they return from war zones, animations are also used to aid their recovery from PTSD, by giving them controlled triggers in a safe environment, in order to desensitise over-alert neural pathways in the brain.(5) Farocki links animation to warfare further by pointing out the operational image technologies’ role in smart bombs, seeing machines and computer-to-computer communication, which don’t make sense to the human eye as representations. These images and ‘ways of seeing’ are intended to have an effect on someone or something, but with no direct relation between the nature of the image and the outcome.(6) In the case of world-building and unbuilding, Bennani and Satterwhite’s manipulation of operational images is a strategy they use in different ways, in order to disrupt and play with the boundary between their invented worlds and the world familiar to the spectator.

Meriem Bennani: Still from Party on the CAPS at the Biennale of Moving Image 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and BIM 2018.

Party on the CAPS

In Party on the CAPS, Meriem Bennani has created a mid-Atlantic island community. This speculative fiction imagines migrants who have tried to teleport themselves to the USA, but who have been intercepted and placed in a transit zone, known as the CAPS. It parallels the real-world trajectories of many migrants, evoking the emotions these groups may experience about leaving home, rebuilding a life, surviving cultural fragmentation, surveillance and life in semi-captivity. It celebrates the resilience of these people, who have built a limbo life from the margins, cast away on an island. Although it started as a detention camp, over a couple of generations the place has developed into a metropolis with its own currency, cuisine and hybrid cultures of traditions preserved from distant homelands plus whatever surplus goods (green, with a crocodile logo) the US sends to the CAPS. Having been intercepted mid teleportation, the migrants’ bodies were left ‘in complete quantum mess’, as a narrator explains. Some have permanent mutations such as large, green ears; others have found their bodies entirely replaced. Meanwhile, access to body improvements is abundant for the privileged rich people in the US, and there are black markets for such things on CAPS for those who can pay in cash. When spectators of this work ‘arrive’ on the island, they do so as tourists, supervised by Fiona, a guide whose crocodile form associates her with the island’s US propaganda machine.

Meriem Bennani: Still from Party on the CAPS at the Biennale of Moving Image 2018. Image courtesy of the artist and BIM 2018.

Visitors move into this world in a controlled manner, guided by Fiona’s introduction to the logic of this place, why bodies look the way they do and how CAPS grew to become an island metropolis. As an official, Fiona cannot be trusted to give objective information – a nod to how other oppressive regimes show tourists the official version but never leave their side in case they discover something off the path. Fiona disappears after a while and the work transitions into Bennani’s documentary style, which allows for intimate glimpses behind closed doors. A group of women take centre stage in this scene – a birthday party for Ghita who is turning 80, although her body looks much younger having undergone an expensive rejuvenation process. They dance, sing, make funny faces, laugh about the troopers (a nickname for the crocodile US immigration officers) and seem comfortable, at ease and well-adjusted to each other’s company.

In an otherwise oppressive reality, the community has made a safe place with this party, where they can relax in their bodies. In this process of teleportation, interception and re-assembly after fragmentation, it’s possible to encounter Muñoz’s notion of queerness: coming close to a sense of community, safety and belonging, but not quite close enough to touch it, yet ‘feel[ing] it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality’.(7) This feeling is powerful enough to start imagining a truly utopian version of the CAPS: no troopers, and freedom and space for all kinds of transitioned bodies living side by side in a community built from re-assembled fragments.

Moving from this utopian place back to the logic of the real world, it is however apparent that on the CAPS, those who have been severely hurt by interception are particularly vulnerable to body image pressure, something US companies and the advertisement industry on CAPS have specialised in preying on. Zip, a company selling second-hand bodies to people who want a new one (without disclosing how these bodies were actually obtained) also offers dodgy second tries at teleporting to the US, for a cash payment. This sounds like a familiar choke-hold: the only way out costs everything you own and you have to be willing to risk your body for it. In creating the ads that run on CAPS, Bennani has used the language of advertising to hack the operational images of commercial desire and self-improvement. These operational images often mask a deeper structural problem with a quicker fix you can pay for yourself (such as a nose job, breast enhancement or liposuction), which blames those problems on the subject’s body rather than on unhealthy beauty standards which reinforce white supremacy, heteronormativity and fat phobia.

On the CAPS, however, Bennani has taken off the mask. She makes clear that the problem lies not with those who desire a new body or a new life, but in a system which has systematised such inequality as its internal logic and driving force and, by doing so she contributes to the ‘unmaking [of] the world that marks these bodies as wrong’, in Halberstam’s words.(8) Seeing the intercepted, re-assembled bodies as queer bodies – transitioned bodies even, having gone from one side to another – they are bodies that are ‘fragmentary and contradictory’, that sound different to what you might expect, or that act differently. They are bodies that unbuild the normative while they rupture binaries and the structures which sort bodies into particular categories of age, race, sexuality, ability, and so on.(9)

The attitude displayed by the islanders towards the authorities makes an exaggerated point about the island’s power dynamics. They hate the troopers, but some go on dates with them to get access to resources. Their clothes reflect different fashion styles, but all are in the same official shade of green. The island has its own currency, yet the American dollar is what gives inhabitants access to certain essentials – and to earn those, you have to do work for the US government. As in many examples of colonisation, the authorities urge their subjects to adopt their own speech, dress, working methods and eating habits, as a means of control and domination. But this can often get turned back on the oppressors.(10) The ambivalence the residents of the CAPS show in mimicking the authorities is almost mocking. They have learnt to adapt so that they can camouflage themselves on two fronts: just enough both to pass with the authorities and to conceal certain things from them. This is also a well-rehearsed queer strategy: passing enough to avoid accidental outing in certain situations, yet still sending out messages that enable the right people to connect.

Jacolby Satterwhite, We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020. HD Colour video and 3D animation with sound. RT: 24:22 min. © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Shrines and We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other

Jacolby Satterwhite’s Shrines and We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other are both part of the series Birds in Paradise which he made in collaboration with his late mother, who left behind a large archive of drawings, texts and songs, which the artist has incorporated in various ways. In both works, highly detailed scenes filled with dancing bodies – warrior-club-goers, some animated, others filmed live – introduce the viewer to a world with a different logic. A familiar queerness is recognisable through layers of symbols common to existing LGBTQIA+ communities, such as movements from ball culture, leather harnesses and BDSM dynamics, combined with references from a wide range of other sources including video games, Yoruba rituals and modernist art.

However, there’s also a longing and aspiration for a different type of queerness. Satterwhite has built separatist spaces in which bodies move like dancers, combatants and healers all at once, in different sizes and shapes – battling patriarchy, the loosening of gun laws and racism from the outside while asserting their own freedom and healing themselves through ritualistic, sexy and at times aggressive movement.

Satterwhite’s works search for healing, and without explicitly revealing where that need for healing comes from, there are signs that cannot be ignored which permeate the semi-utopian states of the built spaces bullets which fly into the frame in Shrines, moving images of KKK gatherings on a TV screen in We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, not to mention the title and the final scene in which Breonna Taylor’s portrait is rendered as a flower bed design.(11)

Jacolby Satterwhite: Still from Shrines, 2020. HD color video and 3D animation with sound © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

In Shrines, space is defined by multiple stages, screens and vantage points, and the action happens everywhere at once. The bodies that populate all these different arenas appear to be in control of their own representation and sexuality. The figures here have such varying sizes and proportions that it is impossible to reference what’s ‘normal’ size. With so many coexisting rooms, stages and perspectives, there seems to be no clearly defined centre stage either – a radical flatness in which everyone and every place have the same importance. The viewer is brought into this world through immersion, yet has the role of someone observing through cruising: moving around to catch some action here and there, but without gaining the total overview that a central, privileged perspective would provide.

In Cruising Utopia, Muñoz urged his readers to ‘cruise the fields of the visual and not so visual in an effort to see in the anticipatory illumination of the utopian’, and to do so with a politicised and ‘renewed and newly animated sense of the social’.(12) Satterwhite’s queer utopia, a seductive piece of alternative world-building, offers a pause from the trauma of the present – a pocket of freedom where the logic and hegemony of the binary heteronormative, capitalist, extractivist and racist society is replaced by a more empowering arrangement. The queer performative gestures and aesthetics are not simply about ‘being’ queer, but about ‘doing’ queerness for the future.(13) Recognising this constructed world as something desirable – a more permitting space to exist in – also connects the experience of the work with the act of longing.

In this work, the image that breaks the illusion of a separate world is a scene of robe-clad men in pointy white hats. Just this one image, hidden among so many other details, brings an unignorable reality into the artist’s attempt to imagine something different. In Shrines, it was the violence of bombs, guns and bullets that intruded on the otherwise safe space. One minute the warm feeling of queerness instils hope; the next you are painfully reminded of the ever-present hierarchies and systems of power, which cause massive inequalities and inject traumas on queer and black bodies on a large scale.

Here, Jack Halberstam’s Cruising Dystopia serves some important nuances. Picking up on Muñoz’ point that ‘new social affects are possible only if we dismantle – rather than simply renovate – the roles and regimes that currently imprison us’, Halberstam centres on the language of architecture, or rather anarchitecture: the unbuilding, undoing and deconstruction.(14) Furthermore, he suggests that a critical point lies in finding the right ways to unbuild to the point where a structure is revealed and taken to the point of collapse, but is yet still not crashing down: only from here, when the walls are down, can we start bringing in whatever is needed to proceed.(15 )

In Satterwhite’s durational dance sequences in both Shrines and We Are In Hell …, whether performed by himself or his created figures, the bodies move restlessly towards the point of collapse, but remain standing. The CGI-rendered fem-bots in Shrines dance like warriors who have to stay agile and fierce as long as the bullets keep on coming, weaponising their ponytails in order to smash all incoming dangers. Other bodies ‘unmake’ any form of established choreography, refusing categorisation and definition by unlinking binary forms of definition and belonging to existing concepts. And as a group, the bodies in the works undo hierarchies between each other. Satterwhite is, as Farocki demonstrated in Serious Games, hacking operational images in a similar way to the US military, only for an entirely different purpose. By creating a safe, even utopian space, the exposure to a small number of triggers can potentially help to retrain the brain to release trauma. This, in combination with the ways in which Satterwhite has built a world that simultaneously pulls away the grounds for categorisation and unbuilds hierarchic relations between bodies constitutes a way of testing out both cognitive and bodily tools for healing, in search of movements, arrangements, sounds and spaces to do so.

The works of Satterwhite and Bennani suggest that the politics of animation in the age of operational images is not reserved for military and machine-to-machine communications. These artists hack the emotionally triggering aspects of certain operational images into empathetic and critical counterparts. In Bennani’s case, she world-builds a place from which she can make more visible those dynamics of our shared reality which need to be undone, bringing down types of logic which trap bodies within a system of oppression through use of humour, satire and realism. By reprogramming advertising, she puts the blame where it belongs while allowing the queered bodies of CAPS to exists as sites of resilience, contradiction and difference. In Satterwhite’s case, he unbuilds familiar vocabularies, spaces and arrangements between bodies in search for a way ahead. In case of both of these artistic examples, world-building and unbuilding go hand in hand.

Liv Brissach was part of the curatorial team for The Machine is Us.

-

1) José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYY Press, 2009), p. 2.

2) Jack Halberstam, ‘Cruising Dystopia: Space, Race, Transition and Anarchitecture’, lecture at Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra, uploaded 24 December 2018 (1), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jkWS9JnmccY.

3) See Farocki in Volker Pantenburg, ‘Working Images: Harun Farocki and the Operational Image’, pp. 49–62 in Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict, edited by Jens Eder, Charlotte Klonk. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2017.

4) TJ Demos, Beyond the World’s End, p. 139.

5) Ibid.

6) Ibid. See also Trevor Paglen, ‘Operational Images’, in e-flux Journal #59 (2014): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61130/operational-images/; and Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Simulation and the Labour of Invisibility: Harun Farocki’s Life Manuals’, Animation 12 (2017): https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1746847717740095

7) Muñoz 2009, p. 2.

8) This resonates with one of Jack Halberstam’s propositions for unmaking in a trans* context: ‘We need to move away from the concept of people who ‘are trapped in the wrong body’ and who require medical interventions and towards a sense of unmaking the world that marks these bodies as wrong.’ Halberstam 2018. See also Jack Halberstam, ‘Unbuilding Gender: Trans* Anarchitectures In and Beyond the Work of Gordon Matta-Clark’, in Places Journal (October 2018 (2)), https://placesjournal.org/article/unbuilding-gender/?cn-reloaded=1.

9) Halberstam 2018 (2).

10) See Homi Bhabha, ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’ in October 28 (Spring, 1984), pp. 125–133.

11) Breonna Taylor was a 26-year-old black medical worker in Louisville, Kentucky who was shot and killed by police officers during a failed police raid on her apartment. See e.g. Richard A. Oppel Jr., Derrick Bryson Taylor and Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, ‘What to Know About Breonna Taylor’s Death’, in The New York Times 26 April 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/article/breonna-taylor-police.html.

12) Muñoz 2009, p. 18.

13) Ibid., p. 2.

14) Halberstam 2018 (1).

15) Ibid.