Should we change the surface of Edvard Munch's paintings?

The artist preferred his paintings with a matte appearance, but over the years conservators have applied varnish on top of the color layers. Can one take the chance to remove it, or is it too risky for the fragile paintings?

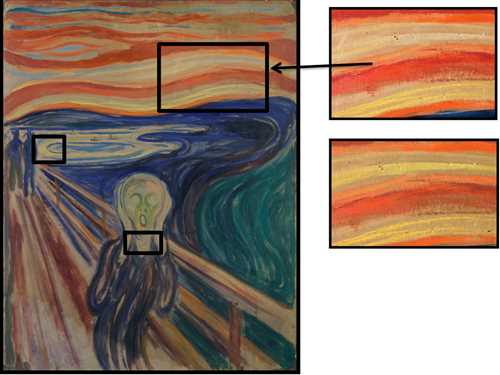

The image sections show how the varnish is yellowed and cracked. The crackles run through the entire varnish layer. But as this poses no immediate risk to the paint layer below, no cleaning of the painting is planned.

There are no reliable sources stating that Edvard Munch coated his paintings with varnish – the transparent, lacquer-like layer that is supposed to protect the paintings from dust, dirt and humidity, and also saturates the colors and creates a smoother surface gloss. On the contrary, there are many indications that he wanted to keep the colors in his paintings as they were originally.

However, a minority of the artist’s paintings have been varnished since the death of Edvard Munch. Why was this done, and would it be too risky to try and remove the varnish?

How is the art best preserved?

MUNCH currently has a well-equipped conservation department where, among other things, they work to preserve and research Munch’s art. An important part of the research is to map out how the artist’s choice of materials and previous treatments of the images have affected the condition of the works today. In this way, we can find suitable methods that best preserve Munch’s art for future generations.

From 2016 to 2018, an interdisciplinary research group at MUNCH studied 23 oil paintings on canvas, all painted by Edvard Munch between 1882 and 1940. Conservation reports showed that the paintings had been applied a special type of ketone-based varnish from the 1950s towards 1980s, both to reduce uneven gloss and to protect the surface from dirt. For 16 of them, the use of AW2, a ketone resin widely used in many conservation studios around Europe, was documented.

Ten of the 16 paintings were examined, and the varnish layer was analyzed with various instruments, both at MUNCH and at other institutions. In addition to ketone resin, wax, animal glue, oils, eggs, pine resin and starch were also found on the canvases. This probably originates from additives in the varnish layer, from the paint layer, and from later used consolidation materials.

Can cleaning damage the paintings?

The main reason why one would choose to remove varnish, is that the layer causes flaking and loose paint of the color layer underneath. Another reason is that the varnish is visually uneven as layer. But removing a varnish layer from paintings that basically have porous color layers does not set the color layers back with the saturation they had when they were painted. This is because the varnish not only lies on the surface, but has drawn into the paint and created a permanent change in the appearance of the colors. This is probably the case with several of Munch’s varnished paintings.

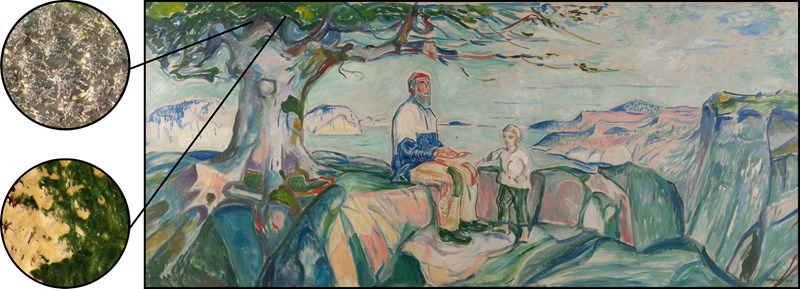

The condition of the color layers is also a challenge. In many of Munch’s paintings, the color layers have a weak attachment to the canvas and are weakly bound due to ageing of binding media. This is due to both Munch’s choice of and experimentation with materials, his working methods, and the storage of the paintings before and after his death. Removal of varnish can in such cases be very comprehensive and challenging.

Where to go from here

The examination of the Munch works showed that the varnish in several of the cases does not pose a risk to the paint layers, nor is it very uneven. In some paintings the varnish is yellowed or very shiny, and in others blanching has occurred - a white coloration that makes the colors in the layers below less obvious. In a couple of the paintings, the varnish has caused scaling and peeling of the color layer.

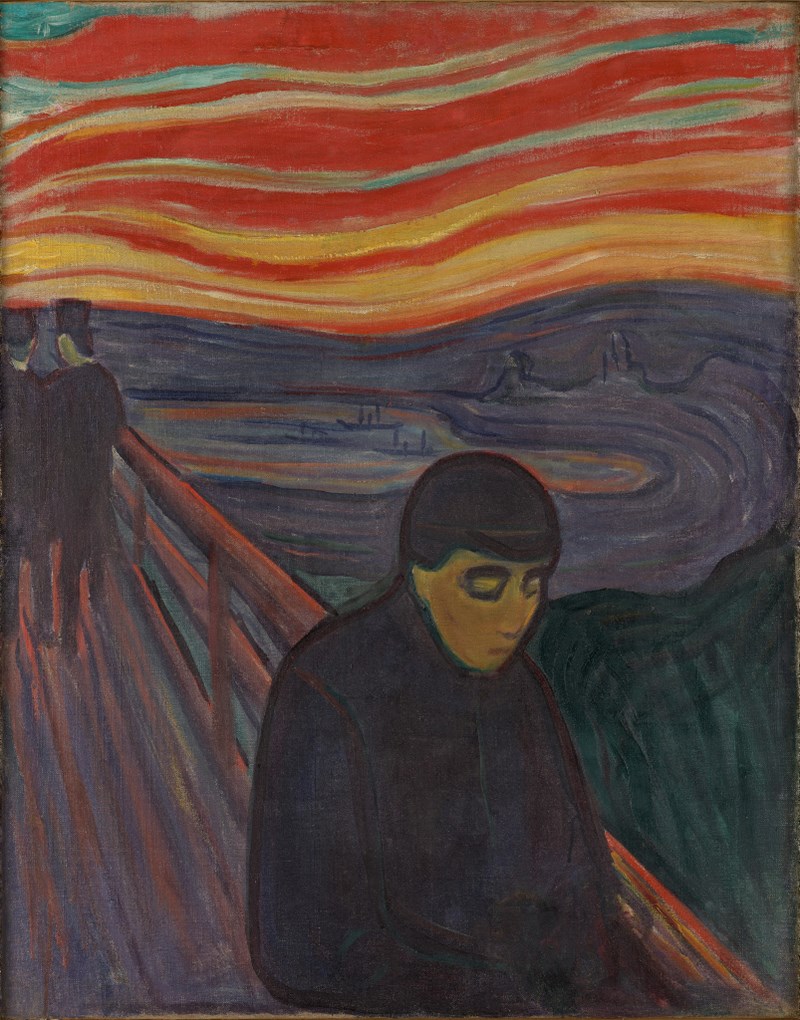

This painting is an example of one of the works where it has been decided to remove the varnish layer because it is to the detriment of the color layer below.

Edvard Munch: Despair, 1894

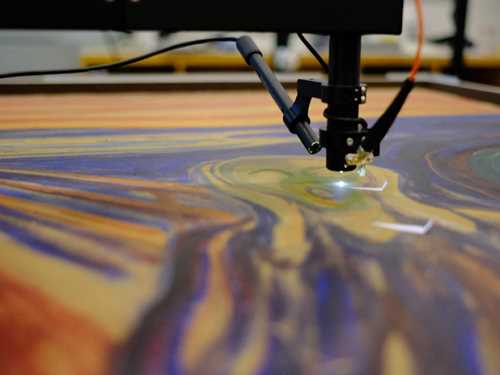

Due to the risk associated with a possible removal, it was decided that in the first instance it is only done in those cases where the varnish poses a structural risk to the paint layers below. This applies, among other things, to the painting Despair from 1894. In this case, an experimentation has begun to test different cleaning methods. The test phase is still ongoing, and further research and testing is needed before the choice of the best method of removal can be determined.

The first phase of the project had Archlab access to libraries and conservation laboratories from three European institutions (Opificio delle Pietre Dure – OPD in Florence, Italy; Centre for Art Technological Studies – CATS in Copenhagen, Denmark; the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands – RCE in Amsterdam, Netherlands), through grant 654028 (H2020-INFRAIA-2014-2015; IPERION).