Munch and melancholy

Several of Munch’s pictures allow us to empathize with different aspects of being alone. He explores melancholy loneliness, but also solitude as a spur for productivity. Perhaps an artist’s view of solitude and isolation is exactly what we need now, in order to process the isolation that our society has experienced?

Edvard Munch: Melancholy. Oil on canvas, 1900–01. Photo © Munchmuseet

During the pandemic, which led to major lockdowns from January 2020, many of us have experienced what it is like to be alone, indoors. Being isolated from other people can be painful and unpleasant. We need other people for emotional closeness, and in our society, we depend on each other for access to food and healthcare, warmth and knowledge. Even so, most people also need to isolate themselves voluntarily. We all experience a desire from time to time to think in private or to withdraw from the hustle and bustle of everyday life.

The ability to create art and to have important ideas has always been associated with people who have the chance to look for answers within their inner mental and emotional worlds.

Being apathetic indoors

In Melancholy (1900–01), one of the paintings on display in Edvard Munch Infinite, we see a young woman sitting indoors. The room appears bright and warm, but the woman has a heavy blanket wrapped around her body.

The potted plant on the table is thriving and flowering. The woman at the table seems to be doing the opposite. She appears not to be present. Her hands lie flaccidly on her lap, her mouth is closed, her eyes are unfocused and she gazes emptily out at the room: her whole body exudes passivity.

She sits in a corner showing no interest either in the world outside – which we glimpse through the window – or in the potted plant on the table. Although she may be present physically, mentally she is in a completely different place. It seems difficult to make contact with her. We are left with a feeling of loneliness.

Ordinarily, we think of rooms as safe places. Edvard Munch challenges this association, however, and experiments with their spatial qualities. He often imbues rooms with psychological dimensions that express their inhabitants’ emotions – whether these are uncertainty, anxiety and fear, or loneliness and isolation.

Many of us remember the dominant feeling in Norway during the national lockdown: of being isolated indoors, of feeling apathetic within the walls of our own homes.

Welcome back, melancholy

Has an expectation grown over the past decades that we should be more outgoing? Most job advertisements are not aimed at people who are quiet or perceived as shy – and the open-plan offices that are becoming more and more common are better suited to collaboration and dialogue, rather than solitary contemplation.

Some people do best alone, while others thrive in the company of others. Introversion and extroversion are modern terms for two personality types. The terms were popularized by the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung in the 1920s. Historically, this categorization can be traced back to ancient medical theories about the four temperaments – sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic and melancholic – of which the first two are characteristic of extroversion and the second two of introversion.

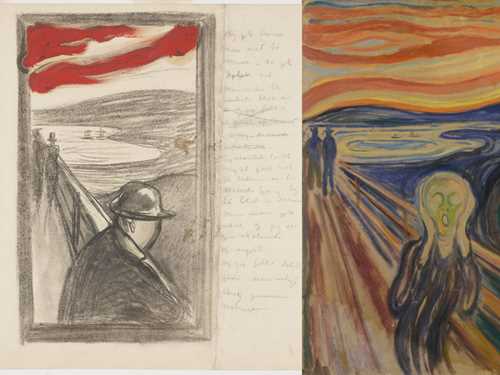

Until the end of the 15th century, a melancholic temperament was considered the least desirable, but then it gradually became associated with various forms of creative activity – a development that culminated in Albrecht Dürer’s visual personification of melancholy in his enigmatic engraving Melencolia I.

Albrecht Dürer: Melancolia I (1514)

This image depicted the creative process for the first time in art history. It shows a dejected, winged figure completely lacking in inspiration, despite the fact that she is surrounded by various tools, repositories of knowledge and other sources of stimulation. Dürer’s image became an important source of inspiration for authors and artists, including Munch.

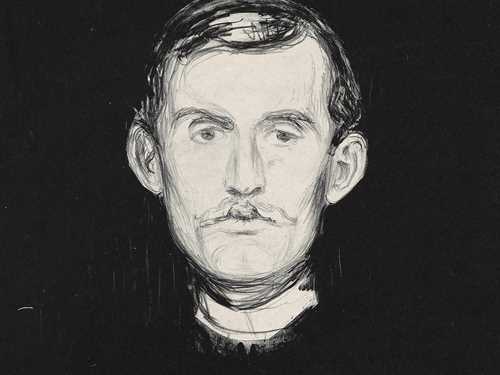

The isolated Munch

Munch had experience of ‘melancholia’, a term sometimes used around the turn of the 20th century to describe severe forms of depression. He knew that such mental states were challenging for everyone involved, both for the sufferer and for those around them.

In 1929, he recalled how he created this painting, Melancholy (1900-1901), saying that he had wanted to record the woman’s “dark, mute unrelenting sorrow”. In the space she exists within, both physically and mentally, the real world is completely meaningless.

Edvard Munch: Melancholy. Oil on canvas, 1900–01. Photo © Munchmuseet

Munch’s text contains a brief reflection on the relative significance of a human life:

What is greatness? – Infinitesimal compared to the stars

What is smallness? Great compared to its atoms

– which are constellations

This text is based on excerpts from the collection catalogue 'Munch Infinite' which will be published in 2022.