These artworks will one day disappear

In the museum collection we have many pictures that are particularly fragile and sensitive to light. Are we right to exhibit them, even if it means that we might someday lose them?

Edvard Munch: Vampire. Oil on canvas, 1893. Photo: Munchmuseet.

Have you ever thought about how artworks may not last forever? Just as old newspapers can crumble into fragile, yellowed fragments, in many cases the same thing happens with art. Materials such as paper, textiles, and pigments deteriorate naturally with age, and exposure to light hastens the process. None of the pictures left to us by Edvard Munch will last forever. Many were already fragile when they entered the Museum’s collection. Perhaps ideally we should have stored them in a cold, dark environment to stop them from disintegrating. Nevertheless, we have chosen to display them, even though this means that the colours in these paintings will probably look different to our children and grandchildren than they do today.

Edvard Munch, Two Girls with Blue Aprons. Oil on canvas, 1904-05. Photo © Munchmuseet

Fading yellow

Have a look at the yellow colour in Munch’s painting Two Little Girls in Blue Aprons. Perhaps you’ve seen it before? It’s known as cadmium yellow and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries its brilliant colour and opacity made it popular with artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. Because the colour is so strong, it is easy to imagine that it will last forever, but this is not the case. In fact, paintings made using this pigment will fade, flake and discolour over time. In addition, they are toxic. These factors led to the development of paints that are more stable and less toxic during the 20th century.

Another colour used by Munch in this painting, red lake, has also changed over the years. Do you think that Munch thought about this in the summer of 1904, when he painted the two girls living next door to his house in Åsgårdstrand?

Edvard Munch: Anxiety. Oil(?) on canvas, 1894. Photo © Munchmuseet

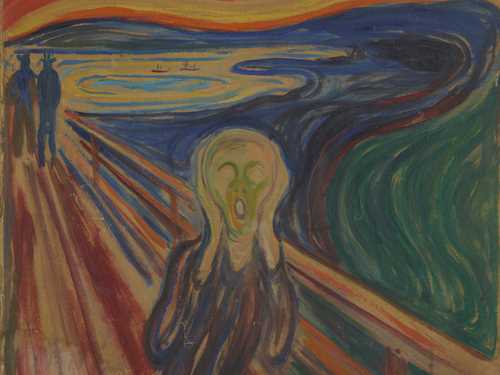

Broken sky

We can see several similarities between Munch’s painting Anxiety (1894) and his most famous image The Scream. There are the same wavy lines in the red and yellow sky, and anxiety is written all over the faces of the people on the bridge, standing against the backdrop of the fjord. Once again Munch has used cadmium yellow, which deteriorates when exposed to light. First individual brushstrokes become white, and then as the ageing process advances they will darken and start to disintegrate. In Anxiety, we can see that a dark crust has formed over the surface. What do you think this painting would look like now if Munch had painted it with the highly durable paints available today?

Edvard Munch: Brothel Scene. Oil on unbound cardboard, 1903. Photo © Munchmuseet

A shadow of itself

Much of the art that you can see at the Museum today used to look rather different. For example, this painting Brothel Scene (1903) – one of a series of paintings by Munch of a German brothel – was created using strong, clear colours. Over time, light has changed its appearance. In several places, the yellow paint has faded and become completely white, while other parts of the image have almost disappeared. In addition, the cardboard panel it was painted on has become much darker. This means that the picture you see today looks quite different from what Munch really wanted.

Edvard Munch: The Hands. Oil and crayon on unbound cardboard, 1893–94. Photo © Munchmuseet

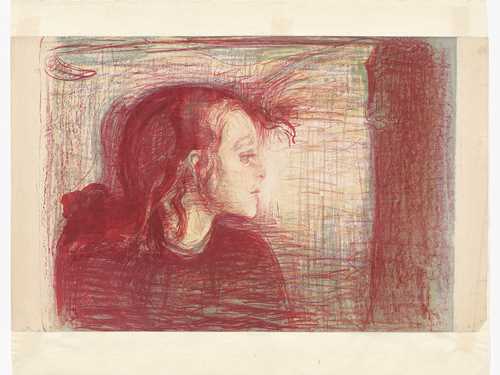

Art in the dark

This painting, known as The Hands, is painted on cardboard. Munch began work on it in 1893, during a period when he often used this instead of canvas. Although his cardboard is often thick and rigid, structurally it is just as delicate as a sheet of paper. It yellows over time – a sign that the cellulose fibres are breaking down and losing their strength. The yellowing of the cardboard will also affect the colours and appearance of the painting. This means that The Hands needs special protection whenever it is exhibited. The lighting in the gallery should be low and the painting must be framed behind special glass that blocks UV light. These measures help prevent further deterioration and extend the life of the painting.

Edvard Munch: Vampire. Oil on canvas, 1893. Photo: Munchmuseet.

Struggle on the surface

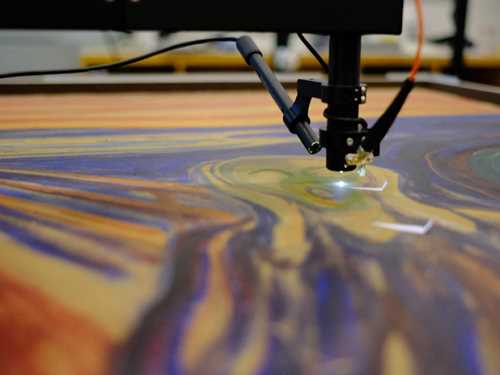

As early as 1952, when the Museum’s staff were sorting out Munch’s estate, they noted that this painted version of Vampire, dating from 1893, was in “extremely poor condition”. With the best intentions, and completely in accordance with the methods used at that time, the painting was glued onto a new canvas and flattened under a heavy weight. Large areas of the painting were retouched and finally the restorers applied two layers of varnish. Today we would consider this type of restoration far too invasive. Putting the painting under a heavy weight has deformed and damaged its surface texture, and the paint is now adhered more firmly to the varnish than to the canvas beneath. This makes the job of conserving the painting very difficult. This version of Vampire were so fragile that we no longer allowed it to leave the Museum, and it were at the top of the Museum´s priority list of paintings in need of research and treatment. This happened in 2023, and you can read more about the restoring process here.

Edvard Munch: Head by Head. Oil on canvas, 1905. Photo © Munchmuseet

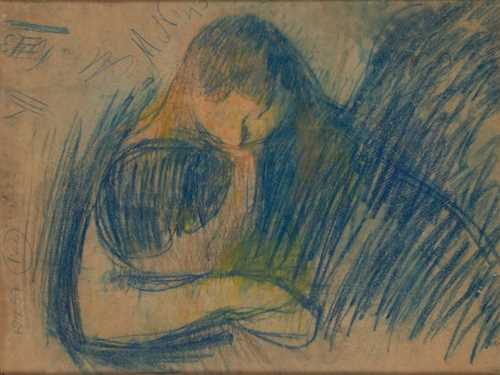

Changing red

This painting, known as Head by Head, is Munch’s first version of a woman’s head next to a man’s head. Here Munch has used various natural red pigments that are broken down by light over the course of time. Some of the pigments fade, while others darken. We don’t know everything about the colours used by Munch, but at the Museum we conduct intensive research in order to understand how we can slow down the rate of deterioration. Sometimes our research leads us to collaborate with other museums. For example, we know that Vincent van Gogh used many of the same types of pigments as Munch. Look at this painting. What do you think the red colours looked like when it was painted in 1905?

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait with Dogs and Little Christmas Tree. Hectography, 1924. Photo © Munchmuseet

On borrowed time

The last time we exhibited this picture, it was behind a curtain that the audience had to pull aside. This is how frail this small work by Munch is. Self-Portrait with Dogs and a Small Christmas Tree from 1924 was printed using a technique known as hectography. Special ink was used to make the drawing, which was then transferred to a gelatine plate that could be used to make several prints of the original. In many ways, this technique was reminiscent of very early photocopiers. The ink used to make hectographs is extremely light sensitive, and even very brief periods of exposure to light will cause it to deteriorate. This means that we have to limit the length of time for which this item is displayed in order to preserve it.

Edvard Munch: Beach. Oil on canvas, 1888. Photo © Munchmuseet

With the best intentions

In traditional painting technique, artists would apply a varnish over the final paint layers in a picture. The varnish saturates the colours and evens out surface gloss. In addition, it is intended as a “sacrificial layer” – a layer that will deteriorate, while the underlying painting is protected. During Munch’s time, many artists abandoned this practice because they wanted to experiment with different artistic expressions. As did Munch, which is why many of his paintings has a dry, matte expression. This was also the case with Beach, which was painted in the summer of 1888, during a stay in Tønsberg. In the 1950s, however, a synthetic varnish was applied. The varnish has a high surface gloss, something that changes Munch`s original intention. And even more serious, this particular type of varnish can damage the original paint layers when it gradually decomposes.

When light causes darkness

These small drawings were made with charcoal and pencil on paper that was slightly acidic. They may have been preparatory sketches for a larger work. Can you see how part of the image titled Man and Woman (1914) is lighter than the rest? This is because the lighter part happened to be lying under another sheet of paper, which prevented it from yellowing. Like Naked Couple, Half-length Figure (1919–21) is painted on a kind of paper that is affected by light and temperature. The paper darkens with age, and its fibres become stiff and brittle. Today, many artists use what is known as acid-free paper. This lasts longer and is more tolerant of different conditions. Perhaps the work of preserving art in the future will involve challenges other than the ones we can predict currently?