A Scream Through Culture

How did Edvard Munch’s The Scream become one of the world’s most famous motifs?

Andy Warhol: The Scream (After Munch), 1984. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

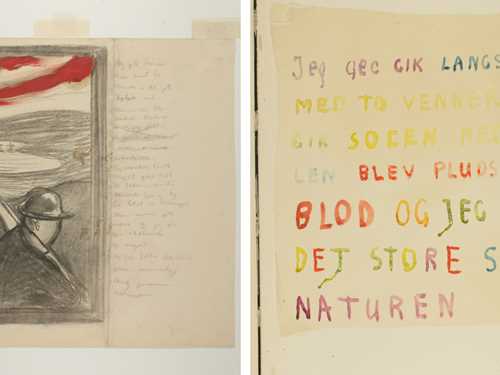

One evening towards the end of the 19th century, Edvard Munch was strolling with two friends at Ekeberg (on the outskirts of Oslo) when he was suddenly overwhelmed with despondency. He leaned against a fence 'tired to death'. He remained there as his friends walked on, and recounted how: '... shaking with Angst – I felt the great Scream in Nature.'

This deeply personal experience would inspire one of the most copied, caricatured and commercialized images in the modern world: The Scream.

From the opening scene of the first Scream movie (1996), where we get to know the famous Scream mask, through a fateful meeting with Casey Becker (Drew Barrymore).

Copyright: Dimension Films

Today this image is found on everything from fridge magnets, ties and mugs to loo rolls and spirit bottles. The figure at the centre of The Scream has turned up in horror movies (the Scream series directed by Wes Craven in the 1990s and 2000s), advertisements and the animated sitcom The Simpsons. It even has its own emoji: more than 100 years after Munch stood shaking at Ekeberg, millions of people use the icon he created to express anxiety when communicating digitally.

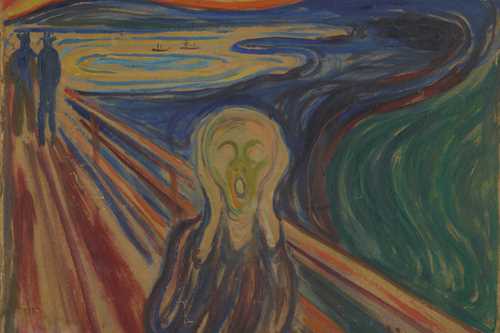

Several attempts, many versions

Greenish skin stretched over a skull, two vacant circles for eyes, a couple of dabs of black paint for nose and a gaping mouth. In various contexts, the figure of The Scream has been associated with things as different as a mummy and a foetus. In fact, when the picture was exhibited in Paris in 1896, one critic suggested changing the title to ‘wandering foetus’.

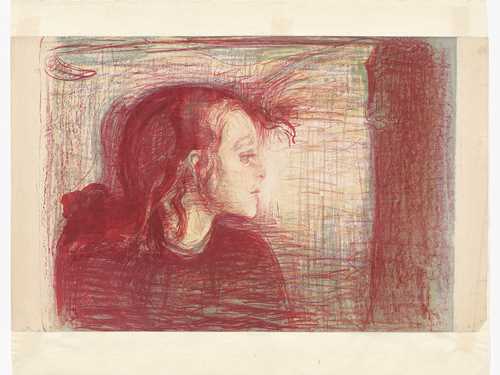

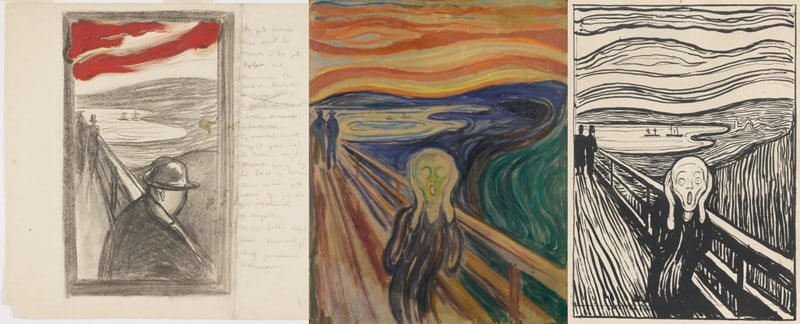

Munch made several attempts before arriving at this famous figure. His initial sketches show an elegantly dressed man gazing across the fjord with an air of melancholy. A fine image, but not particularly iconic. Gradually the figure becomes more anonymous and sexless, both universal and non-human, before turning towards the viewer in its distinctive pose. The non-specific appearance of the final motif permits everyone, regardless of age, gender, or cultural background, to recognize in it something of themselves.

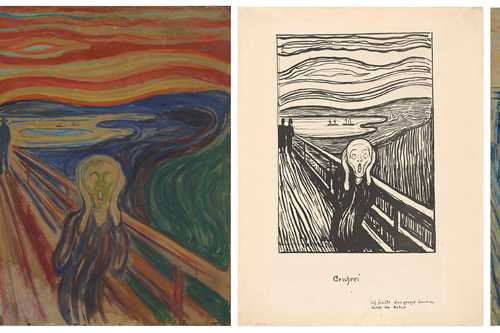

Contrary to what many people believe, The Scream is not a single work, but a motif that exists in several versions. Two of them are paintings, of which one belongs to the National Museum and one to MUNCH. One of the few Scream pictures in private ownership, a pastel, was sold for nearly USD 120 million in 2012. This made it one of the most expensive works in art history. Munch himself seems to have been happy with the image: he used a black-and-white printed version as an illustration for exhibition catalogues, art journals and book covers, and the central figure also appeared on the front page of the workers’ newspaper Social-Demokraten in 1898.

Even so, it was only after Munch’s death in 1944 that the popularity of the image really took off.

Munch as a brand

Early in the 1950s, several of Munch’s paintings, including the Munch Museum’s version of The Scream, were sent on an extensive international tour. At the same time, the first English-language book about Munch was published. All this was in the years following World War II. The atom bomb had been invented, divorce statistics were skyrocketing, and many feared a new war. Munch, who was sensitive to the psychological effects of the anonymity of urban life and alienation engendered by capitalism, was well in tune with the spirit of the age. In 1961, The Scream adorned the front cover of Time magazine in connection with an article on “The Anatomy of Angst”.

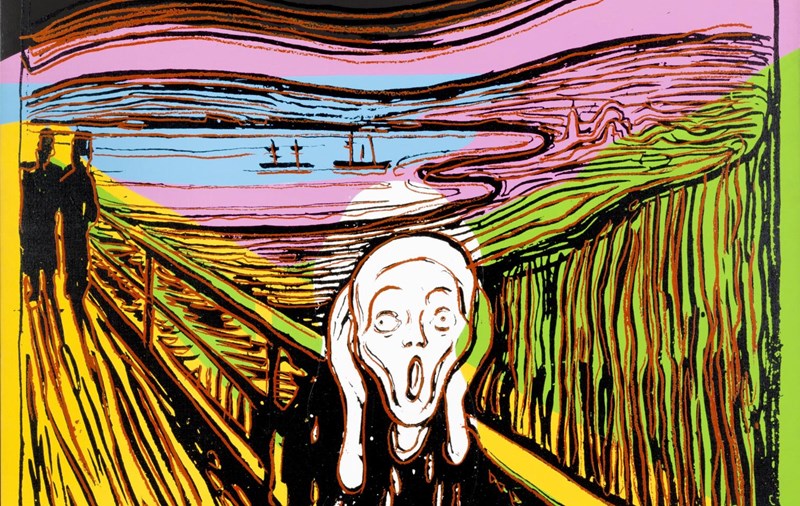

Andy Warhol: The Scream (After Munch), 1984. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Photo: Sparebankstiftelsen DNB

Over the next few decades, The Scream found its way into both advertising and film. The motif’s celebrity status was cemented by the American artist Andy Warhol. In 1984, Warhol created a series of screenprints titled The Scream (after Munch) – brightly coloured large-scale copies of Munch’s lithograph. Warhol was famous for using images from popular culture in his art – everything from movie stars and politicians to everyday objects. By reproducing The Scream, he boosted the iconic status of the image, and showed at the same time that it could be seen as a mass-produced consumer product on a par with Mickey Mouse or a can of tomato soup.

A robbery hits the world’s headlines

Sometimes one has to lose something – not just once, but twice – to understand its value. In 1994, in the early morning hours of the day the Winter Olympics were due to open at Lillehammer, the National Museum’s version of The Scream was stolen. Two people climbed up a ladder, broke a windowpane, hopped through the window, took the painting off the wall and left by the same route. They left a postcard of a painting of three laughing men bearing the handwritten message “Many thanks for the poor security”. The whole operation took 50 seconds. Fortunately, the painting was recovered three months later.

Ten years later, The Scream once again played the lead role in a criminal investigation. This time the circumstances were far more dramatic. In 2004, two men, masked and carrying guns, entered the Munch Museum at Tøyen and stole both The Scream and Madonna in full view of incredulous museum visitors. The robbery was headline news all over the world. There was little visual material for the media, however, apart from a short video of the robbers fleeing from the Museum, captured by a quick-thinking Austrian tourist. Accordingly, The Scream became the most-used image in reports about the case.

Photo: NTB/Scanpix

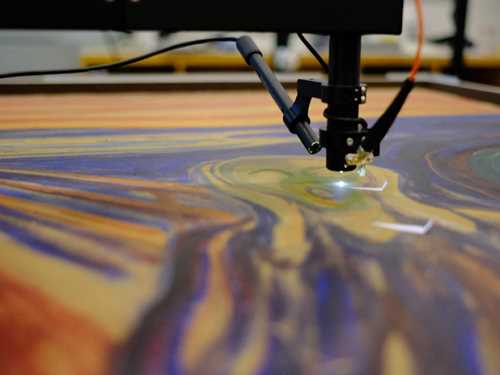

Two years later the paintings were recovered. Given the circumstances they were in good condition, although The Scream had acquired a stain in the lower-left corner, a legacy of the robbery, which proved impossible to remove. The painting’s expressive power was undiminished, however. Munch’s own comment that a good painting with 10 holes is better than a bad painting with no holes took on renewed significance.

CoronaVirus crisis, Brexit and climate fears

The media storm that erupted in the wake of the two robberies contributed to strengthening Munch’s status internationally, and also here in Norway. A few days after The Scream and The Madonna were once again on view at Tøyen, the news about the new museum at Bjørvika was made public.

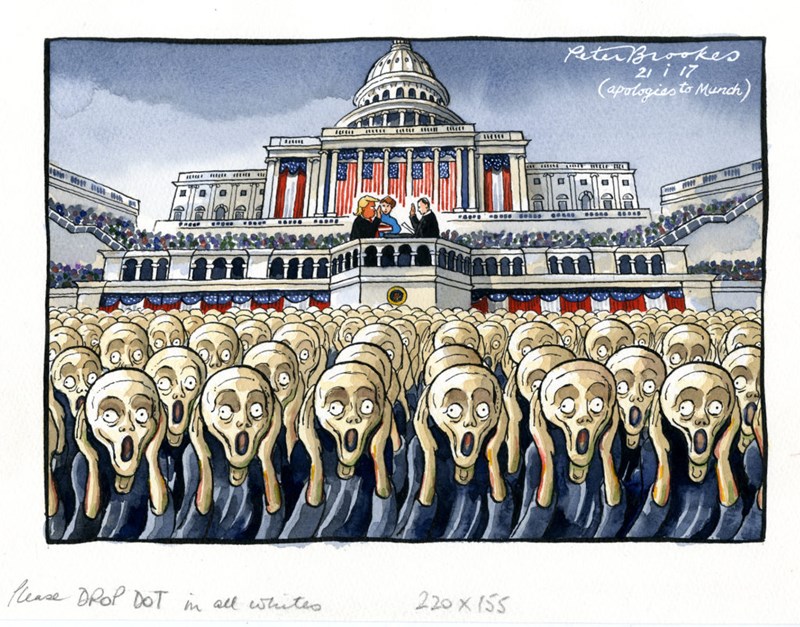

Today, it may seem as though the Scream motif is more relevant than ever. When the British cartoonist Peter Brookes wanted to express what many people were feeling when Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, he turned to Munch’s image.

Peter Brookes (f. 1943), The Scream, 2017.

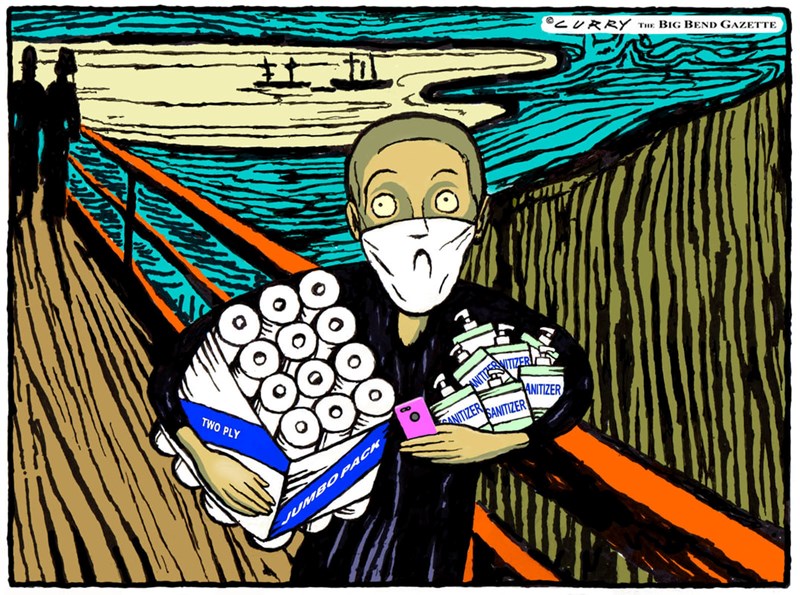

In the context of the corona crisis, the motif has constantly emerged as a picture of the collective anxiety in the face of a global pandemic. Not without humor, however: The Scream figure has been depicted with both face masks and carrying toilet paper and sanitizers.

© tomcurrystudio.com

The image also appears in political demonstrations against everything from right-wing populism, anti-abortion legislation and Brexit to global warming. As an image for the climate crisis, it is particularly apposite. In contrast to what many people believe, it is the landscape, not the figure, that is screaming, according to Munch’s own texts: “... felt the great Scream in nature”.

The continuing popularity of The Scream demonstrates the universal nature of the image. The new Munchmuseet is anticipating half-a-million visitors each year. According to Innovation Norway, 60–70 per cent of these visitors will be tourists whose main reason for visiting the Museum will be to see The Scream. Does this mean that The Scream is Munch’s best work? Would it be more or less powerful if one were looking at the image for the very first time? There are no definite answers to these questions. What is certain, however, is that the image Munch created continues to speak to the whole world, regardless of age, religion, gender or education.